Welcome to this workshop on containers and OpenShift! Today, we will use a hosted OCP environment provided by your instructor, along with these instructions, as we journey from simple Linux containers to advanced container orchestration using Red Hat OpenShift. Let's begin!

- Container Fundamentals

- Get Started with Containers

- Manage Your Containers

- Understand Container Registries

- Run Container Images with Hosts (Optional)

- Architect a Better Environment (Optional)

- Next Up

If you understand Linux, you probably already have 85% of the knowledge you need to understand containers. If you understand how processes, mounts, networks, shells and daemons work - commands like ps, mount, ip addr, bash, httpd and mysqld - then you just need to understand a few extra primitives to become an expert with containers. Remember that all of the things that you already know today still apply: from security and performance to storage and networking, containers are just a different way of packaging and delivering Linux applications. There are four basic primitives to learn to get you from Linux administrator to feeling comfortable with containers:

Once, you understand the basic four primitives, there are some advanced concepts that will be covered in future labs including:

- Container Standards: Understanding OCI, CRI, CNI, and more

- Container Tools Ecosystem - Podman, Buildah, Skopeo, cloud registries, etc

- Production Image Builds: Sharing and collaborating between technical specialists (performance, network, security, databases, etc)

- Intermediate Architecture: Production environments

- Advanced Architecture: Building in resilience

- Container History: Context for where we are at today

Covering all of this material is beyond the scope of any live training, but we will cover the basics, and students can move on to other labs not covered in the classroom. These labs are available online at http://learn.openshift.com/subsystems.

Now, let's start with the introductory lab, which covers these four basic primitives:

Container images are really just tar files. Seriously, they are tar files, with an associated JSON file. Together we call these an Image Bundle. The on-disk format of this bundle is defined by the OCI Image Specification. All major container engines including Podman, Docker, RKT, CRI-O and containerd build and consume these bundles.

But let's dig into three concepts a little deeper:

1. Portability: Since the OCI standard governs the images specification, a container image can be created with Podman, pushed to almost any container registry, shared with the world, and consumed by almost any container engine including Docker, RKT, CRI-O, containerd and, of course, other Podman instances. Standardizing on this image format lets us build infrastructure like registry servers which can be used to store any container image, be it RHEL 6, RHEL 7, RHEL8, Fedora, or even Windows container images. The image format is the same no matter which operating system or binaries are in the container image. Notice that Podman can download a Fedora image, uncompress it, and store it in the local /var/lib/containers image storage even though this isn't a Fedora container host:

podman pull quay.io/fedora/fedora

2. Compatibility: This addresses the content inside the container image. No matter how hard you try, ARM binaries in a container image will not run on POWER container hosts. Containers do not offer compatibility guarantees; only virtualization can do that. This compatibility problem extends to processor architecture, and also versions of the operating system. Try running a RHEL 8 container image on a RHEL 4 container host -- that isn't going to work. However, as long as the operating systems are reasonably similar, the binaries in the container image will usually run. Note that executing basic commands with a Fedora image work even though this isn't a Fedora container host:

podman run -t quay.io/fedora/fedora cat /etc/redhat-release

3. Supportability: This is what vendors can support. This is about investing in testing, security, performance, and architecture as well as ensuring that images and binaries are built in a way that they run correctly on a given set of container hosts. For example, Red Hat supports RHEL 6, UBI 7, and UBI 8 container images on both RHEL 7 and RHEL 8 container hosts (CoreOS is built from RHEL bits). Red Hat cannot guarantee that every permutation of container image and host combination on the planet will work. It would expand the testing and analysis matrix resources at a non-linear growth rate. To demonstrate, run a Red Hat Universal Base Image (UBI) container on this container host. If this was a RHEL container host, this would be completely supported (sorry, only CentOS hosts available for this lab environment :-) so not supported, but you get the point):

podman run -t registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi cat /etc/redhat-release

Analyzing portability, compatibility, and supportability, we can deduce that a RHEL 7 image will work on RHEL 7 host perfectly. The code in both were designed, compiled, and tested together. The Product Security Team at Red Hat is analyzing CVEs for this combination, performance teams are testing RHEL 7 web servers, with a RHEL 7 kernel, etc, etc. The entire machine of software creation and testing does its work in this configuration with programs and kernels compiled, built and tested together. Matching versions of container images and hosts inherit all of this work:

However, there are limits. Red Hat can't guarantee that RHEL 5, Fedora, and Alpine images will work like they were intended to on a RHEL 7 host. The container image standards guarantee that the container engine will be able to ingest the images, pulling them down and caching them locally. But, nobody can guarantee that the binaries in the container images will work correctly. Nobody can guarantee that there won't be strange CVEs that show up because of the version combinations (yeah, that's "a thing"), and of course, nobody can guarantee the performance of the binaries running on a kernel for which it wasn't compiled. That said, many times, these binaries will appear to just work.

This leads us to supportability as a concept separate from portability and compatibility. This is the ability to guarantee to some level that certain images will work on certain hosts. Red Hat can do this between selected major versions of RHEL for the same reason that we can do it with the RHEL Application Compatibility Guide. We take special precautions to compile our programs in a way that doesn't break compatibility, we analyze CVEs, and we test performance. A bare minimum of testing, security, and performance can go a long way in ensuring supportability between versions of Linux, but there are limits. One should not expect that container images from RHEL 9, 10, or 11 will run on RHEL 8 hosts.

Alright, now that we have sorted out the basics of container images, let's move on to registries...

Registries are really just fancy file servers that help users share container images with each other. The magic of containers is really the ability to find, run, build, share and collaborate with a new packaging format that groups applications and all of their dependencies together.

Container images make it easy for software builders to package software, as well as provide information about how to run it. Using metadata, software builders can communicate how users can and should run their software, while providing the flexibility to also build new things based on existing software.

Registry servers just make it easy to share this work with other users. Builders can push an image to a registry, allowing users and even automation like CI/CD systems to pull it down and use it thousands or millions of times. Some registries like the Red Hat Container Catalog offer images which are highly curated, well tested, and enterprise grade. Others, like Quay.io, are cloud-based registries that give individual users public and private spaces to push their own images and share them with others. Curated registries are good for partners who want to deliver solutions together (eg. Red Hat and CrunchyDB), while cloud-based registries are good for end users collaborating on work.

Now, let's move on to container hosts...

To understand the Container Host, we must analyze the layers that work together to create a container. They include:

A container engine can loosely be described as any tool which provides an API or CLI for building or running containers. This started with Docker, but also includes Podman, Buildah, rkt, and CRI-O. A container engine accepts user inputs, pulls container images, creates some metadata describing how to run the container, then passes this information to a container Runtime.

A container runtime is a small tool that expects to be handed two things - a directory often called a root filesystem (or rootfs), and some metadata called config.json (or spec file). The most common runtime runc is the default for every container engine mentioned above. However, there are many innovative runtimes including katacontainers, gvisor, crun, and railcar.

The kernel is responsible for the last mile of container creation, as well as resource management during its running lifecycle. The container runtime talks to the kernel to create the new container with a special kernel function called clone(). The runtime also handles talking to the kernel to configure things like cgroups, SELinux, and SECCOMP (more on these later). The combination of kernel technologies invoked are defined by the container runtime, but there are very recent efforts to standardize this in the kernel.

Containers are just regular Linux processes that were started as child processes of a container runtime instead of by a user running commands in a shell. All Linux processes live side by side, whether they are daemons, batch jobs or user commands - the container engine, container runtime, and containers (child processes of the container runtime) are no different. All of these processes make requests to the Linux kernel for protected resources like memory, RAM, TCP sockets, etc.

The goal of this exercise is to understand the difference between base images and multi-layered images (repositories). Also, we'll try to understand the difference between an image layer and a repository.

Let's take a look at some base images. We will use the Podman history command to inspect all of the layers in these repositories. Notice that these container images have no parent layers. These are base images, and they are designed to be built upon. First, let's look at the full ubi7 base image:

podman history registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi:latest

Now, create a new file named Dockerfile and add the content below

FROM registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi

RUN echo "Hello world" > /tmp/newfile

RUN echo "Hello world" > /tmp/newfile2

RUN echo "Hello world" > /tmp/newfile3

RUN echo "Hello world" > /tmp/newfile4

RUN echo "Hello world" > /tmp/newfile5

Now, build a new multi-layered image:

podman build -t ubi7-change -f ~/Dockerfile

Do you see the newly created ubi7-change tag?

podman images

Can you see all of the layers that make up the new image/repository/tag? This command even shows a short summary of the commands run in each layer. This is very convenient for exploring how an image was made.

podman history ubi7-change

Notice that the first image ID (bottom) listed in the output matches the registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi image. Remember, it is important to build on a trusted base image from a trusted source (aka have provenance or maintain chain of custody). Container repositories are made up of layers, but we often refer to them simply as "container images" or containers. When architecting systems, we must be precise with our language, or we will cause confusion to our end users.

Now we are going to inspect the different parts of the URL that you pull. The most common command is something like this, where only the repository name is specified:

podman inspect ubi7/ubi

But, what's really going on? Well, similar to DNS, the Podman command line is resolving the full URL and TAG of the repository on the registry server. The following command will give you the exact same results:

podman inspect registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi:latest

You can run any of the following commands, and you will get the exact same results as well:

podman inspect registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi:latest

podman inspect registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi

podman inspect ubi7/ubi:latest

podman inspect ubi7/ubi

Now, let's build another image, but give it a tag other than "latest":

podman build -t ubi7:test -f ~/Dockerfile

Now, notice there is another tag.

podman images

Now try the resolution trick again. What happened?

podman inspect ubi7

It failed, but why? Try again with a complete URL:

podman inspect ubi7:test

Notice that Podman resolves container images similar to DNS resolution. Each container engine is different, and Docker will actually resolve some things Podman doesn't because there is no standard on how image URIs are resolved. If you test long enough, you will find many other caveats to namespace, repository, and tag resolution. Generally, it's best to always use the full URI, specifying the server, namespace, repository, and tag. Remember this when building scripts. Containers seem deceptively easy, but you need to pay attention to details.

Now, we will take a look at what's inside the container image. Java is particularly interesting because it uses glibc, even though most people don't realize it. We will use the ldd command to prove it, which shows you all of the libraries that a binary is linked against. When a binary is dynamically linked (libraries loaded when the binary starts), these libraries must be installed on the system, or the binary will not run. In this example, in particular, you can see that getting a JVM to run with the exact same behavior requires compiling and linking in the same way. Stated another way, all Java images are not created equal:

podman run -it registry.access.redhat.com/jboss-eap-7/eap70-openshift ldd -v -r /usr/lib/jvm/java-1.8.0-openjdk/jre/bin/java

Notice that dynamic scripting languages are also compiled and linked against system libraries:

podman run -it registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi ldd /usr/bin/python

Inspecting a common tool like "curl" demonstrates how many libraries are used from the operating system. First, start the RHEL Tools container. This is a special image that Red Hat releases with all of the tools necessary for troubleshooting in a containerized environment. It's rather large, but quite convenient:

podman run -it registry.access.redhat.com/rhel7/rhel-tools bash

Take a look at all of the libraries curl is linked against:

ldd /usr/bin/curl

Let's see what packages deliver those libraries. It seems as if it's both OpenSSL and the Network Security Services libraries. When there is a new CVE discovered in either OpenSSL or NSS, a new container image will need to be built to patch it:

rpm -qf /lib64/libssl.so.10

rpm -qf /lib64/libssl3.so

Exit the rhel-tools container:

exit

It's a similar story with Apache and most other daemons and utilities that rely on libraries for security or deep hardware integration:

podman run -it registry.access.redhat.com/rhscl/httpd-24-rhel7 bash

Inspect mod_ssl Apache module:

ldd /opt/rh/httpd24/root/usr/lib64/httpd/modules/mod_ssl.so

Once again, we find a library provided by OpenSSL:

rpm -qf /lib64/libcrypto.so.10

Exit the httpd24 container:

exit

What does this all mean? Well, it means you need to be ready to rebuild all of your container images any time there is a security vulnerability in one of the libraries inside it.

The goal of this exercise is to understand the basics of trust when it comes to Registry Servers and Repositories. This requires quality and provenance - this is just a fancy way of saying that:

- You must download a trusted thing

- You must download from a trusted source

Each of these is necessary, but neither alone is sufficient. This has been true since the days of downloading ISO images for Linux distros. Whether evaluating open source libraries or code, prebuilt packages (RPMs or Debs), or Container Images, we must:

-

Determine if we trust the image by evaluating the quality of the code, people, and organizations involved in the project. If it has enough history, investment, and actually works for us, we start to trust it.

-

Determine if we trust the registry, by understanding the quality of its relationship with the trusted project - if we download something from the offical GitHub repo, we trust it more than from a fork by user Haxor5579. This is true with ISOs from mirror sites and with image repositories built by people who aren't affiliated with the underlying code or packages.

There are plenty of examples where people ignore one of the above and get hacked. In a previous lab, we learned how to break the URL down into registry server, namespace and repository.

From a security perspective, it's much better to remotely inspect and determine if we trust an image before we download it, expand it, and cache it in the local storage of our container engine. Every time we download an image, and expose it to the graph driver in the container engine, we expose ourselves to potential attack. First, let's do a remote inspect with Skopeo (can't do that with Podman because of the client/server nature):

sudo dnf install -y skopeo

skopeo inspect docker://registry.fedoraproject.org/fedoraExamine the JSON. There's really nothing in there that helps us determine if we trust this repository. It "says" it was created by the Fedora project ("vendor": "Fedora Project") but we have no idea if that is true. We have to move on to verifying that we trust the source, then we can determine if we trust the thing.

There's a lot of talk about image signing, but the reality is, most people are not verifying container images with signatures. What they are actually doing is relying on SSL to determine that they trust the source, then inferring that they trust the container image. Lets use this knowledge to do a quick evaluation of the official Fedora registry:

curl -I https://registry.fedoraproject.org

Since you are on a Red Hat Enterprise Linux box with the right keys, the output should look like this:

HTTP/2 200

date: Thu, 25 Apr 2019 17:50:25 GMT

server: Apache/2.4.39 (Fedora)

strict-transport-security: max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains; preload

x-frame-options: SAMEORIGIN

x-xss-protection: 1; mode=block

x-content-type-options: nosniff

referrer-policy: same-origin

last-modified: Thu, 25 Apr 2019 17:25:08 GMT

etag: "1d6ab-5875e1988dd3e"

accept-ranges: bytes

content-length: 120491

apptime: D=280

x-fedora-proxyserver: proxy10.phx2.fedoraproject.org

x-fedora-requestid: XMHzYeZ1J0RNEOvnRANX3QAAAAE

content-type: text/htmlYou can also discern that the certicate is valid and managed by Red Hat, which helps a bit:

curl 2>&1 -kvv https://registry.fedoraproject.org | grep subjectThink carefully about what we just did. Even visually validating the certificate gives us some minimal level of trust in this registry server. In a real world scenario, rememeber that it's the container engine's job to check these certificates. That means that Systems Administrators need to distribute the appropriate CA certificates in production. Now that we have inspected the certificate, we can safely pull the trusted repository (because we trust the Fedora project built it right) from the trusted registry server (because we know it is managed by Fedora/Red Hat):

podman pull registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora

Now, lets move on to evaluate some trickier repositories and registry servers...

Let's learn how to evaluate Container Images and Registry Servers.

First, let's start with what we already know: there is often a full functioning Linux distro inside a container image. That's because it's useful to leverage existing packages and the dependency tree already created for it. This is true whether running on bare metal, in a virtual machine, or in a container image. It's also important to consider the quality, frequency, and ease of consuming updates in the container image.

To analyze the quality, we are going to leverage existing tools - which is another advantage of consuming a container images based on a Linux distro. To demonstrate, let's examine images from four different Linux distros - CentOS, Fedora, Ubuntu, and Red Hat Enterprise Linux. Each will provide differing levels of information:

podman run -it docker.io/centos:7.0.1406 yum updateinfoCentOS does not provide Errata for package updates, so this command will not show any information. This makes it difficult to map CVEs to RPM packages. This, in turn, makes it difficult to update the packages which are affected by a CVE. Finally, this lack of information makes it difficult to score a container image for quality. A basic workaround is to just update everything, but even then, you are not 100% sure which CVEs you patched.

podman run -it registry.fedoraproject.org/fedora dnf updateinfoFedora provides decent meta data about package updates, but does not map them to CVEs either. Results will vary on any given day, but the output will often look something like this:

Last metadata expiration check: 0:00:07 ago on Mon Oct 8 16:22:46 2018.

Updates Information Summary: available

5 Security notice(s)

1 Moderate Security notice(s)

2 Low Security notice(s)

5 Bugfix notice(s)

2 Enhancement notice(s)podman run -it docker.io/ubuntu:trusty-20170330 /bin/bash -c "apt-get update && apt list --upgradable"Ubuntu provides information at a similar quality to Fedora, but again does not map updates to CVEs easily. The results for this specific image should always be the same because we are purposefully pulling an old tag for demonstration purposes.

podman run -it registry.access.redhat.com/ubi9/ubi:9.4-947 yum updateinfo securityRegrettably, we do not have the active Red Hat subscriptions necessary to analyze the Red Hat Universal Base Image (UBI) on the command line, but the output would look more like the following if we did:

RHSA-2019:0679 Important/Sec. libssh2-1.4.3-12.el7_6.2.x86_64

RHSA-2019:0710 Important/Sec. python-2.7.5-77.el7_6.x86_64

RHSA-2019:0710 Important/Sec. python-libs-2.7.5-77.el7_6.x86_64Notice the RHSA-: column - this indicates the Errata and its level of importance. This errata can be used to map the update to a particular CVE, giving you and your security team confidence that a container image is patched for any particular CVE. Even without a Red Hat subscription, we can analyze the quality of a Red Hat image by looking at the Red Hat Container Cataog and using the Contianer Health Index:

We should see something similar to:

Now, that we have taken a look at several container images, we are going to start to look at where they came from and how they were built - we are going to evaluate four registry servers - Fedora, DockerHub, Bitnami and the Red Hat Container Catalog:

- Click: registry.fedoraproject.org

The Fedora registry provides a very basic experience. You know that it is operated by the Fedora project, so the security should be pretty similar to the ISOs you download. That said, there are no older versions of images, and there is really no stated policy about how often the images are patched, updated, or released.

DockerHub provides "official" images for a lot of different pieces of software including things like CentOS, Ubuntu, Wordpress, and PHP. That said, there really isn't standard definition for what "official" means. Each repository appears to have their own processes, rules, time lines, lifecycles, and testing. There really is no shared understanding what official images provide an end user. Users must evaluate each repository for themselves and determine whether they trust that it's connected to the upstream project in any meaningful way.

Similar to DockerHub, there is not a lot of information linking these repostories to the upstream projects in any meaningful way. There is not even a clear understanding of what tags are available, or should be used. Again, no policy information and users are pretty much left to sift through GitHub repositories to have any understanding of how they are built of if there is any lifecycle guarantees about versions. You are pretty much left to just trusting that Bitnami builds containers the way you want them...

- Click: https://catalog.redhat.com

The Red Hat Container catalog is setup in a completely different way than almost every other registry server. There is a tremendous amount of information about each respository. Poke around and notice how this particular image has a warning associated. For the point of this exercise, we are purposefully looking at an older image with known vulnerabilities. That's because container images age like cheese, not like wine. Trust is fleeting and older container images age just like servers which are rarely or never patched.

Now take a look at the Container Health Index scoring for each tag that is available. Notice, that the newer the tag, the better the letter grade. The Red Hat Container Catalog and Container Health Index clearly show you that the newer images have a less vulnerabiliites and hence have a better letter grade. To fully understand the scoring criteria, check out Knowledge Base Article. This is a completely unique capability provided by the Red Hat Container Catalog because container image Errata are produced tying container images to CVEs.

Knowing what you know now:

- How would you analyze these container repositories to determine if you trust them?

- How would you rate your trust in these registries?

- Is brand enough? Tooling? Lifecycle? Quality?

- How would you analyze repositories and registries to meet the needs of your company?

These questions seem easy, but they're really not. It really makes you revisit what it means to "trust" a container registry and repository...

Next, we are going to focus on how Container Engines cache Repositories on the container host. There is a little known or understood fact - whenever you pull a container image, each layer is cached locally, mapped into a shared filesystem - typically overlay2 or devicemapper. This has a few implications. First, this means that caching a container image locally has historically been a root operation. Second, if you pull an image, or commit a new layer with a password in it, anybody on the system can see it, even if you never push it to a registry server.

Now, let's take a look at Podman container engine. It pulls OCI compliant, Docker compatible images:

podman info | grep -A4 graphRoot

First, you might be asking yourself, what the heck is d_type?. Long story short, it's a filesystem option that must be supported for overlay2 to work properly as a backing store for container images and running containers.

With Podman, as well as most other container engines on the planet such as Docker, image layers are mapped one for one to some kind of storage, be it thinp snapshots with devicemapper, or directories with overlay2.

This has implications on how you move container images from one registry to another. First, you have to pull it and cache it locally. Then you have to tag it with the URL, Namespace, Repository and Tag that you want in the new registry. Finally, you have to push it. This is a convoluted mess, and in a later lab, we will investigate a tool called Skopeo that makes this much easier.

For now, you understand enough about registry servers, repositories, and how images are cached locally. Let's move on.

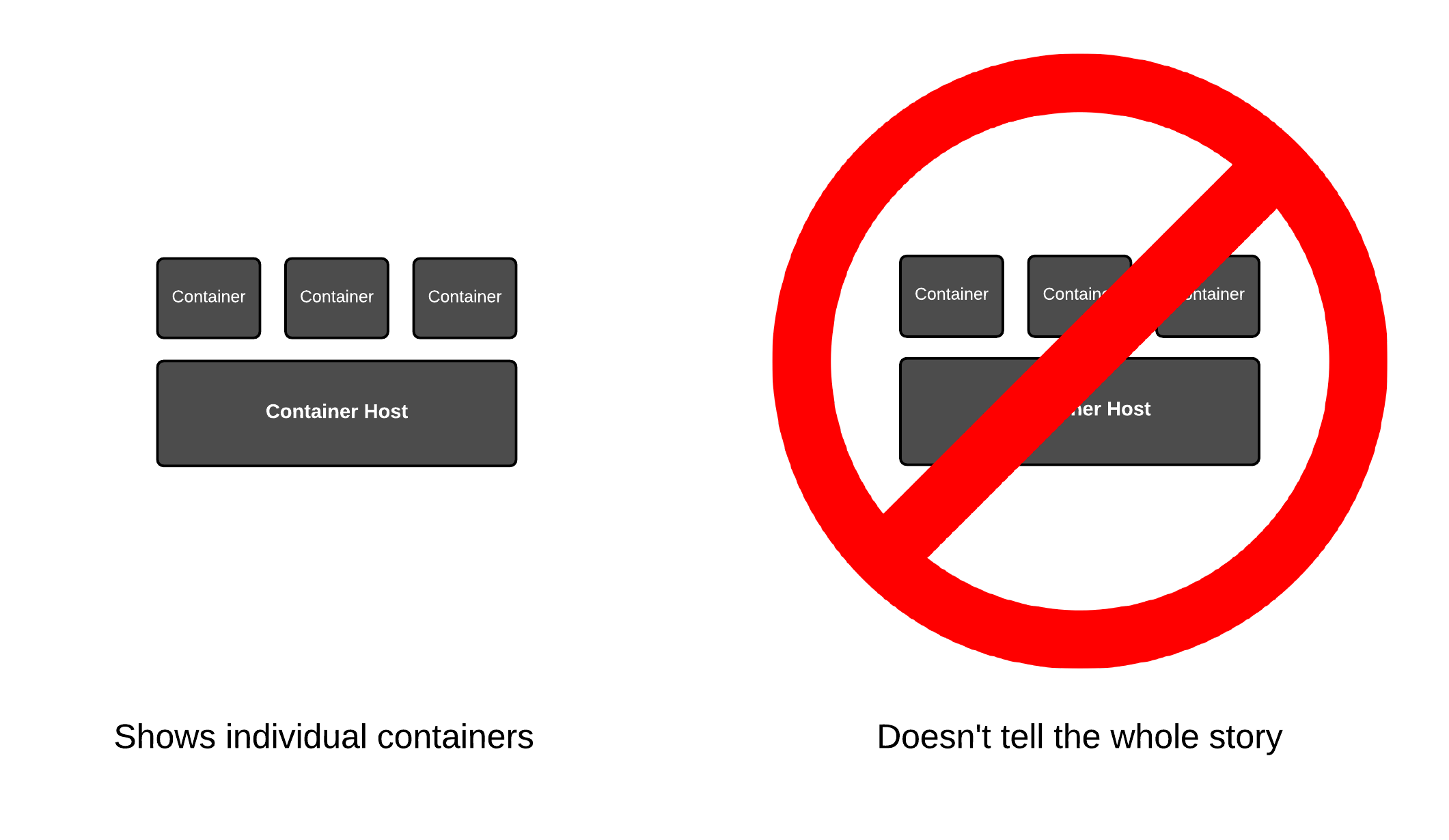

If you just do a quick Google search, you will find tons of architectural drawings which depict things the wrong way or only tell part of the story. This leads the innocent viewer to come to the wrong conclusion about containers. One might suspect that even the makers of these drawings have the wrong conclusion about how containers work and hence propogate bad information. So, forget everything you think you know.

How do people get it wrong? In two main ways:

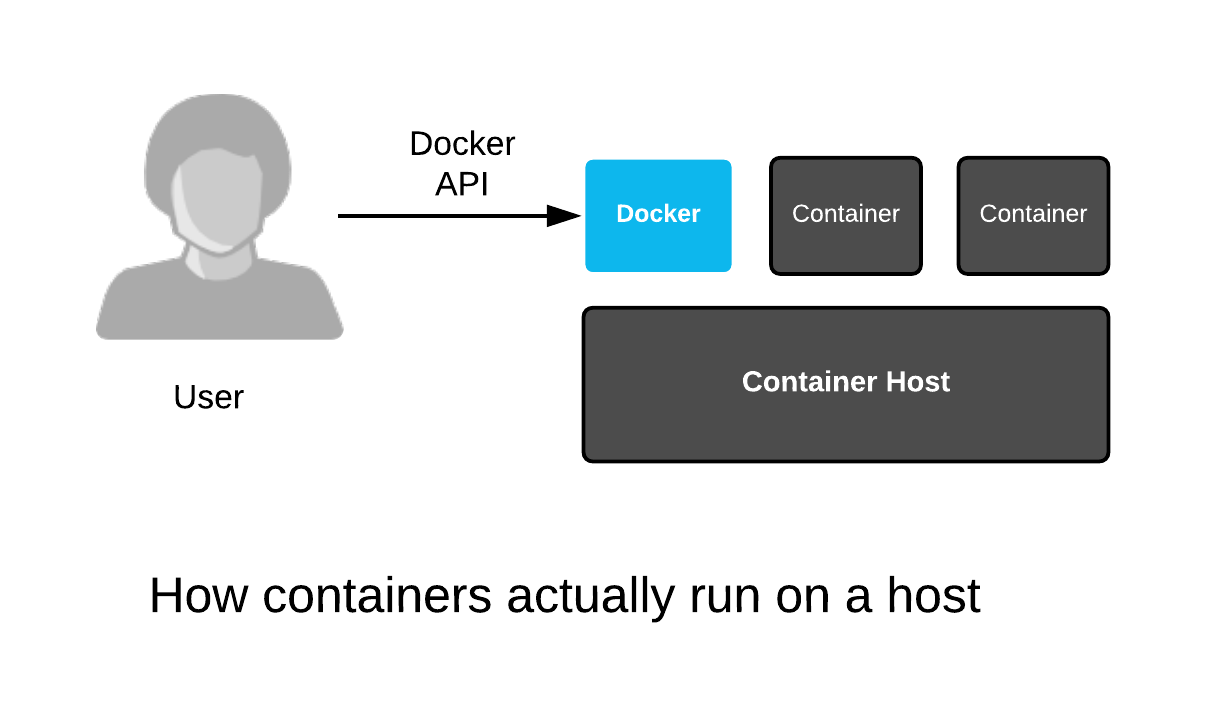

First, most of the architectural drawings above show the Podman daemon as a wide blue box stretched out over the container host. The containers are shown as if they are running on top of the Podman daemon. This is incorrect - containers don't run on Podman. The Podman engine is an example of a general purpose container engine. Humans talk to container engines and container engines talk to the kernel - the containers are actually created and run by the Linux kernel. Even when drawings do actually show the right architecture between the container engine and the kernel, they never show containers running side by side:

Second, when drawings show containers are Linux processes, they never show the container engine side by side. This leads people to never think about these two things together, hence users are left confused with only part of the story:

For this lab, let’s start from scratch. In the terminal, let's start with a simple experiment - start three containers which will all run the top command:

podman run -td registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi top

podman run -td registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi top

podman run -td registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi top

Now, let's inspect the process table of the underlying host:

ps -efZ | grep -v grep | grep " top"

Notice that we started each of the top commands in containers. We started three with Podman, but they are still just a regular process which can be viewed with the trusty old ps command. That's because containerized processes are just fancy Linux processes with extra isolation from normal Linux processes. A simplified drawing should really look something like this:

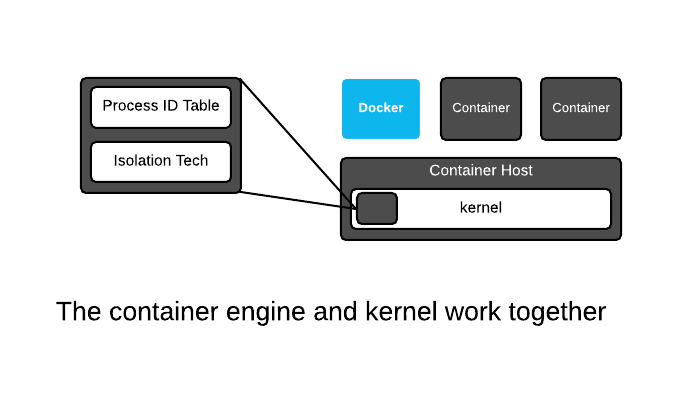

In the kernel, there is no single data structure which represents what a container is. This has been debated back and forth for years - some people think there should be, others think there shouldn't. The current Linux kernel community philosophy is that the Linux kernel should provide a bunch of different technologies, ranging from experimental to very mature, enabling users to mix these technologies together in creative, new ways. And, that's exactly what a container engine (Docker, Podman, CRI-O, etc) does - it leverages kernel technologies to create, what we humans call, containers. The concept of a container is a user construct, not a kernel construct. This is a common pattern in Linux and Unix - this split between lower level (kernel) and higher level (userspace) technologies allows kernel developers to focus on enabling technologies, while users experiment with them and find out what works well.

The Linux kernel only has a single major data structure that tracks processes - the process id table. The ps command dumps the contents of this data structure. But, this is not the total definition of a container - the container engine tracks which kernel isolation technologies are used, and even what data volumes are mounted. This information can be thought of as metadata which provides a definition for what we humans call a container. We will dig deeper into the technical underpinnings, but for now, understand that containerized processes are regular Linux processes which are isolated using kernel technologies like namespaces, SELinux and cgroups. This is sometimes described as "sand boxing" or "isolation" or an "illusion" of virtualization.

In the end though, containerized processes are just regular Linux processes. All processes live side by side, whether they are regular Linux processes, long lived daemons, batch jobs, interactive commands which you run manually, or containerized processes. All of these processes make requests to the Linux kernel for protected resources like memory, RAM, TCP sockets, etc. We will explore this deeper in later labs, but for now, commit this to memory...

Next, let's gain a basic understanding of SELinux/sVirt. Run the following commands:

podman run -dt registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi sleep 10

podman run -dt registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi sleep 10

sleep 3

ps -efZ | grep container_t | grep sleep

Example Output:

system_u:system_r:container_t:s0:c228,c810 root 18682 18669 0 03:30 pts/0 00:00:00 sleep 10

system_u:system_r:container_t:s0:c184,c827 root 18797 18785 0 03:30 pts/0 00:00:00 sleep 10

Notice that each container is labeled with a dynamically generated Multi Level Security (MLS) label. In the example above, the first container has an MLS label of c228,c810 while the second has a label of c184,c827. Since each of these containers is started with a different MLS label, they are prevented from accessing each other's memory, files, etc.

SELinux doesn't just label the processes, it must also label the files accessed by the process. Make a directory for data, and inspect the SELinux label on the directory. Notice the type is set to "user_tmp_t" but there are no MLS labels set:

mkdir /tmp/selinux-testls -alhZ /tmp/selinux-test/Example Output:

drwxr-xr-x. root root system_u:object_r:container_file_t:s0:c177,c734 .

drwxrwxrwt. root root system_u:object_r:tmp_t:s0 ..Now, run the following command a few times and notice the MLS labels change every time. This is sVirt at work:

podman run -t -v /tmp/selinux-test:/tmp/selinux-test:Z registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi ls -alhZ /tmp/selinux-testFinally, look at the MLS label set on the directory, it is always the same as the last container that was run. The :Z option auto-labels and bind mounts so that the container can access and change files on the mount point. This prevents any other process from accessing this data and is done transparently to the end user.

ls -alhZ /tmp/selinux-test/The goal of this exercise is to gain a basic understanding of how containers prevent using each other's reserved resources. The Linux kernel has a feature called cgroups (abbreviated from control groups) which limits, accounts for, and isolates the resource usage (CPU, memory, disk I/O, network, etc.) of processes. Normally, these control groups would be set up by a system administrator (with cgexec), or configured with systemd (systemd-run --slice), but with a container engine, this configuration is handled automatically.

To demonstrate, run two separate containerized sleep processes:

podman run -dt registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi sleep 10

podman run -dt registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi sleep 10

sleep 3

for i in $(podman ps | grep sleep | awk '{print $1}' | grep [0-9]); do find /sys/fs/cgroup/ | grep $i; doneNotice how each containerized process is put into its own cgroup by the container engine. This is quite convenient, similar to sVirt.

Now let's gain a basic understanding of SECCOMP. Think of a SECCOMP as a firewall which can be configured to block certain system calls. While optional, and not configured by default, this can be a very powerful tool to block misbehaved containers. Take a look at this sample below. Create a file named chmod.json and copy this JSON into it.

{

"defaultAction": "SCMP_ACT_ALLOW",

"syscalls": [

{

"name": "fchmodat",

"action": "SCMP_ACT_ERRNO"

}

]

}Now, run a container with this profile and test if it works.

podman run -it --security-opt seccomp=~/chmod.json registry.access.redhat.com/ubi7/ubi chmod 777 /etc/hosts

Notice how the chmod system call is blocked.

Let's now turn to the three Open Containers Initiative (OCI) specificaitons that govern finding, running, building and sharing containers - image, runtime, and distribution. At the highest level, containers are two things - files and processes - at rest and running. First, we will take a look at what makes up a container repository on disk, then we will look at what directives are defined to create a running container.

If you are interested in a slightly deeper understanding, take a few minutes to look at the OCI work, it's all publicly available in GitHub repositories:

- The Image Specification Overview

- The Runtime Specification Abstract

- The Distributions Specification Use Cases

Now, let's run some experiments to better understand these specifications.

First, lets take a quick look at the contents of a container repository once it's uncompressed. Create a working directory for our experiment, then make sure the Fedora image is cached locally:

mkdir fedora

cd fedora

podman pull fedora

Now, export the image to a tar, file and extract it:

podman save -o fedora.tar fedora

tar xvf fedora.tar

Finally, let's take a look at three important parts of the container repository - these are the three major pieces that can be found in a container repository when inspected:

- Manifest - Metadata file which defines layers and config files to be used.

- Config - Config file which is consumed by the container engine. This config file is combined with user input specified at start time, as well as defaults provided by the container engine to create the runtime Config.json. This file is then handed to the continer runtime (runc) which communicates with the Linux kernel to start the container.

- Image Layers - tar files which are typically typically gzipped. They are merged together when the container is run to create a root file system which is mounted.

In the Manifest, you should see one or more Config and Layers entries:

(Note if jq is not installed, run sudo dnf install -y jq first)

jq . manifest.json

In the Config file, note that all of the metadata is similar to command line options in Docker & Podman:

cat $(cat manifest.json | awk -F 'Config' '{print $2}' | awk -F '["]' '{print $3}') | jq

Each Image Layer is just a tar file. When all of the necessary tar files are extracted into a single directory, they can be mounted into a container's mount namespace:

tar tvf $(cat manifest.json | awk -F 'Layers' '{print $2}' | awk -F '["]' '{print $3}')

The take away from inspecting the three major parts of a container repository is that they are really just a clever use of tarballs. Now, that we understand what is on disk, lets move onto the runtime.

This specification governs the format of the file that is passed to the container runtime. Every OCI compliant runtime will accept this file format, including runc, crun, Kata, gVisor, Railcar, etc. Typically, this file is constructed by a container engine such as CRI-O, Podman, containerd or Docker. These files can be created manually, but it's a tedious process. Instead, we are going to do couple of experiments so that you can get a feel for this file without having to create one manually.

Before we begin our experiments, you need to have a basic understanding of the inputs that go into creating this spec file:

-

The container image comes with a config.json which provides some input. We inspected this file in the last section on the image specification. These inputs are a combination of things provided by the image builder (Example:

Cmd) as well as defaults specified by the build tool (Example:architecture). The inputs specified at build time can be thought of as a way for the image builder to communicate with the image consumer about how the image should be run. -

The container engine itself also provides some default inputs. Some of these can be configured in the configuration for the container engine (Example: SECCOMP profiles), some are dynamically generated by the container engine (Example: sVirt/SELinux contexts, or Bind Mounts - aka the copy on write layer which gets mounted in the container's namespace), while others are hardcoded into the container engine (Example: the default namespaces to utilize).

-

The command line options specified by the user of the container engine (or robot in Kubernetes' case) can override many of the defaults provided in the image or by the container engine. Some of these are simple things like bind mounts (Example:

-v /data:/data) or more complex like security options (Example:--privilegedwhich disables a lot of technologies in the kernel).

Now, let's start with some experiments. Being the reference implementation for the runtime specifiction, runc has the ability to create a very simple spec file. Let's create one and take a quick look at the fairly simple set of directives:

sudo dnf install -y runc

cd ~/fedora && runc spec

jq . config.json

The simple file created by runc is a good introduction, but to truly understand the breadth of what a container engine does, we need to look at a more complex example. Podman has the ability to create a container and generate a spec file without actually starting the container:

podman create --name fedora -t fedora bash

podman init fedora

The "podman init" command generates a config.json and we can take a look at it in /home/student/.local/share/containers/storage/overlay-containers:

cat $(find /home/student/.local/share/containers/storage/overlay-containers/ | grep $(podman ps --no-trunc -q | tail -n 1)/userdata/config.json) | jq

Take a minute to browse through the json output. See if you can spot directives which come from the container image, the container engine, and the user.

Now that we have a basic understanding of the runtime spec file, let's move on to starting a container...

Let's now learn how to use the container runtime to communicate with the Linux kernel to start a container. You will build a simple set of metadata, and start a container. This will give you insight into what the container engine is actually doing every time you run a command.

To get runc to start a new container we need two main things:

-

A filesystem to mount (often called a RootFS)

-

A config.json file

First, lets create (or steal) a RootFS, which is really nothing more than a Linux distribution extracted into a directory. Podman makes this ridiculously easy to to do. The following command will fire up a container, get the ID, mount it, then rsync the filesystem contents out of it into a directory:

rsync -av $(podman mount $(podman create fedora bash))/ ~/fedora/rootfs/

We have ourselves a RootFS directory to work with, check it out:

ls -alh ~/fedora/rootfs

Now that we have a RootFS, lets create a spec file and modify it:

rm -rf ~/fedora/config.json

runc spec -b ~/fedora/

sed -i 's/"terminal": true/"terminal": false/' ~/fedora/config.json

Now, we have ourselves a full "bundle" which is a collequial way of referring to the RootFS and Config together in one directory:

ls -alh ~/fedora

First, let's create an empty container. This essentially creates the user space definition for the container, but no processes are spawned yet:

runc create -b ~/fedora/ fedora

List the created containers:

runc list

Now, lets execute a bash process in the container, so that we can see what's going on. Essentially, any number of processes can be exec'ed in the same namespace and they will all have access to the same PID table, Mount table, etc:

runc exec --tty fedora bash

It looks just like a normal container you would see with Podman, Docker or CRI-O inside of Kubernetes. That's because it is:

ls

Now, get out of the container:

exit

Delete it and verify that things are cleaned up. You may notice other containers running, that may be because other containers on the system are running in CRI-O, Podman, or Docker:

runc delete fedora

runc list

In summary, we have learned how to create containers with a terse little program called runc. This is the exact same program used by every major container engine on the planet. In production, you would never create containers like this, but it's useful to understand what is going on under the hood in CRI-O, Podman and Docker. When you run into new projects like Kata, gVisor, and others, you will now understand exactly how and where they fit in into the software stack.

Congratulations! You just completed the first module of today's workshop. Please continue to Container Tools.