forked from lgatto/2016-02-25-adv-programming-EMBL

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 0

/

Copy path01-intro.Rmd

679 lines (506 loc) · 13.6 KB

/

01-intro.Rmd

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

---

title: "Part I: Introduction"

author: "Laurent Gatto"

---

## Overview

- Coding style(s)

- Interactive use and programming

- Environments

- Tidy data

- Computing on the language

## Introduction

> Computers are cheap, and thinking hurts. -- Uwe Ligges

Simplicity, readability and consistency are a long way towards

robust code.

## Coding style(s)

Why?

> Good coding style is like using correct punctuation. You can manage

> without it, but it sure makes things easier to read.

-- Hadley Wickham

for **consistency** and **readability**.

## Which one?

- [Bioconductor](http://master.bioconductor.org/developers/how-to/coding-style/)

- [Hadley Wickham](http://r-pkgs.had.co.nz/style.html)

- [Google](http://google.github.io/styleguide/Rguide.xml)

- ...

## Examples

- Place spaces around all infix operators (`=`, `+`, `-`, `<-`, etc., but *not* `:`)

and after a comma (`x[i, j]`).

- Spaces before `(` and after `)`; not for function.

- Use `<-` rather than `=`.

- Limit your code to 80 characters per line

- Indentation: do not use tabs, use 2 (HW)/4 (Bioc) spaces

- Function names: use verbs

- Variable names: camelCaps (Bioc)/ `_` (HW) (but not a `.`)

- Prefix non-exported functions with a ‘.’ (Bioc).

- Class names: start with a capital

- Comments: `# ` or `## ` (from emacs)

## [`formatR`](https://cran.rstudio.com/web/packages/formatR/index.html)

```{r, eval=TRUE}

library("formatR")

tidy_source(text = "a=1+1;a # print the value

matrix ( rnorm(10),5)",

arrow = TRUE)

```

## [`BiocCheck`](http://bioconductor.org/packages/devel/bioc/html/BiocCheck.html)

```

$ R CMD BiocCheck package_1.0.0.tgz

```

```

* Checking function lengths................

The longest function is 677 lines long

The longest 5 functions are:

* Checking formatting of DESCRIPTION, NAMESPACE, man pages, R source,

and vignette source...

* CONSIDER: Shortening lines; 616 lines (11%) are > 80 characters

long.

* CONSIDER: Replacing tabs with 4 spaces; 3295 lines (60%) contain

tabs.

* CONSIDER: Indenting lines with a multiple of 4 spaces; 162 lines

(2%) are not.

```

## Style changes over time

## Ineractive use vs programming

Moving from using R to programming R is *abstraction*, *automation*,

*generalisation*.

## Interactive use vs programming: `drop`

```{r, eval=FALSE}

head(cars)

head(cars[, 1])

head(cars[, 1, drop = FALSE])

```

## Interactive use vs programming: `sapply/lapply`

```{r, eval=FALSE}

df1 <- data.frame(x = 1:3, y = LETTERS[1:3])

sapply(df1, class)

df2 <- data.frame(x = 1:3, y = Sys.time() + 1:3)

sapply(df2, class)

```

Rather use a form where the return data structure is known...

```{r, eval=FALSE}

lapply(df1, class)

lapply(df2, class)

```

or that will break if the result is not what is exected

```{r, eval=FALSE}

vapply(df1, class, "1")

vapply(df2, class, "1")

```

## Semantics

- *pass-by-value* copy-on-modify

- *pass-by-reference*: environments, S4 Reference Classes

```{r, eval=FALSE}

x <- 1

f <- function(x) {

x <- 2

x

}

x

f(x)

x

```

## Environments

### Motivation

- Data structure that enables *scoping* (see later).

- Have reference semantics

- Useful data structure on their own

### Definition (1)

An environment associates, or *binds*, names to values in memory.

Variables in an environment are hence called *bindings*.

## Creating and populate environments

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e <- new.env()

e$a <- 1

e$b <- LETTERS[1:5]

e$c <- TRUE

e$d <- mean

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e$a <- e$b

e$a <- LETTERS[1:5]

```

- Objects in environments have unique names

- Objects in different environments can of course have identical names

- Objects in an environment have no order

- Environments have parents

## Definition (2)

An environment is composed of a *frame* that contains the name-object

bindings and a parent (enclosing) environment.

## Relationship between environments

Every environment has a parent (enclosing) environment

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e <- new.env()

parent.env(e)

```

Current environment

```{r, eval=FALSE}

environment()

parent.env(globalenv())

parent.env(parent.env(globalenv()))

```

Noteworthy environments

```{r, eval=FALSE}

globalenv()

emptyenv()

baseenv()

```

All parent of `R_GlobalEnv`:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

search()

as.environment("package:stats")

```

Listing objects in an environment

```{r, eval=FALSE}

ls() ## default is R_GlobalEnv

ls(envir = e)

ls(pos = 1)

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

search()

```

Note: Every time a package is loaded with `library`, it is inserted in

the search path after the `R_GlobalEnv`.

## Accessors and setters

- In addition to `$`, one can also use `[[`, `get` and `assign`.

- To check if a name exists in an environmet (or in any or its

parents), one can use `exists`.

- Compare two environments with `identical` (not `==`).

**Question** Are `e1` and `e2` below identical?

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e1 <- new.env()

e2 <- new.env()

e1$a <- 1:10

e2$a <- e1$a

```

What about `e1` and `e3`?

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e3 <- e1

e3

e1

identical(e1, e3)

```

## Locking environments and bindings

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e <- new.env()

e$a <- 1

e$b <- 2 ## add

e$a <- 10 ## modify

```

Locking an environment stops from adding new bindings:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

lockEnvironment(e)

e$k <- 1

e$a <- 100

```

Locking bindings stops from modifying bindings with en envionment:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

lockBinding("a", e)

e$a <- 10

e$b <- 10

lockEnvironment(e, bindings = TRUE)

e$b <- 1

```

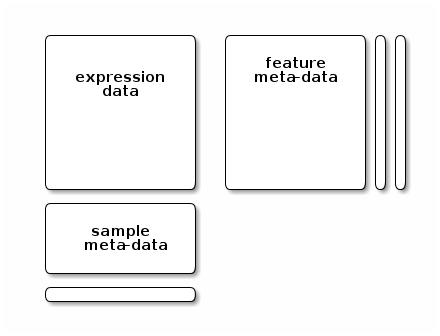

## Exercise

Reproduce the following environments and variables in R.

## Where is a symbol defined?

`pryr::where()` implements the regular scoping rules to find in which

environment a binding is defined.

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e <- new.env()

e$foo <- 1

bar <- 2

where("foo")

where("bar")

where("foo", env = e)

where("bar", env = e)

```

## Lexical scoping

[Lexical comes from *lexical analysis* in computer science, which is

the conversion of characters (code) into a sequence of meaningful (for

the computer) tokens.]

**Definition**: Rules that define how R looks up values for a given name/symbol.

- Objects in environments have unique names

- Objects in different environments can of course have identical names.

- If a name is not found in the current environment, it is looked up

in the parent (enclosing) from.

- If it is not found in the parent (enclosing) frame, it is looked up

in the parent's parent frame, and so on...

```{r, eval=FALSE}

search()

mean <- function(x) cat("The mean is", sum(x)/length(x), "\n")

mean(1:10)

base::mean(1:10)

rm(mean)

mean(1:10)

```

## Assignments

- `<-` assigns/creates in the current environment

- `<<-` (deep assignment) never creates/updates a variable in the

current environment, but modifies an existing variable in the

current or first enclosing environment where that name is defined.

- If `<<-` does not find the name, it will create the variable in the

global environment.

```{r, eval=TRUE}

library("fortunes")

fortune(174)

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

rm(list = ls())

x

f1 <- function() x <<- 1

f1()

x

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

f2 <- function() x <<- 2

f2()

x

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

f3 <- function() x <- 10

f3()

x

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

f4 <- function(x) x <-10

f4(x)

x

```

## Using environments

Most environments are created when creating and calling

functions. They are also used in packages as *package* and *namespace*

environments.

There are several reasons to create then manually.

- Reference semantics

- Avoiding copies

- Package state

- As a hashmap for fast name lookup

## Reference semantics

```{r, eval=TRUE}

modify <- function(x) {

x$a <- 2

invisible(TRUE)

}

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

x_l <- list(a = 1)

modify(x_l)

x_l$a

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

x_e <- new.env()

x_e$a <- 1

modify(x_e)

x_e$a

```

Tip: when setting up environments, it is advised to set to parent

(enclosing) environment to be `emptyenv()`, to avoid accidentally

inheriting objects from somewhere else on the search path.

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e <- new.env()

e$a <- 1

e

parent.env(e)

parent.env(e) <- emptyenv()

parent.env(e)

e

```

or directly

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e <- new.env(parent.env = empty.env())

```

### Exercise

What is going to happen when we access `"x"` in the four cases below?

```{r, eval=FALSE}

x <- 1

e1 <- new.env()

get("x", envir = e1)

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

get("x", envir = e1, inherits = FALSE)

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e2 <- new.env(parent = emptyenv())

get("x", envir = e2)

```

```{r, eval=FALSE}

get("x", envir = e1, inherits = FALSE)

```

## Avoiding copies

Since environments have reference semantics, they are not copied.

When passing an environment as function argument (directly, or as part

of a more complex data structure), it is **not** copied: all its

values are accessible within the function and can be persistently

modified.

```{r, eval=FALSE}

e <- new.env()

e$x <- 1

f <- function(myenv) myenv$x <- 2

f(e)

e$x

```

This is used in the `eSet` class family to store the expression data.

```{r, eval=FALSE}

library("Biobase")

getClass("eSet")

getClass("AssayData")

new("ExpressionSet")

```

## Preserving state in packages

Explicit envirionments are also useful to preserve state or define

constants-like variables in a package. One can then set getters and

setters for users to access the variables within that private

envionment.

#### Use case

Colour management in [`pRoloc`](https://github.com/lgatto/pRoloc/blob/master/R/environment.R):

```{r, eval=FALSE}

.pRolocEnv <- new.env(parent=emptyenv(), hash=TRUE)

stockcol <- c("#E41A1C", "#377EB8", "#238B45", "#FF7F00", "#FFD700", "#333333",

"#00CED1", "#A65628", "#F781BF", "#984EA3", "#9ACD32", "#B0C4DE",

"#00008A", "#8B795E", "#FDAE6B", "#66C2A5", "#276419", "#CD8C95",

"#6A51A3", "#EEAD0E", "#0000FF", "#9ACD32", "#CD6090", "#CD5B45",

"#8E0152", "#808000", "#67000D", "#3F007D", "#6BAED6", "#FC9272")

assign("stockcol", stockcol, envir = .pRolocEnv)

getStockcol <- function() get("stockcol", envir = .pRolocEnv)

setStockcol <- function(cols) {

if (is.null(cols)) {

assign("stockcol", stockcol, envir = .pRolocEnv)

} else {

assign("stockcol", cols, envir = .pRolocEnv)

}

}

```

and in plotting functions (we will see the `missing` in more details later):

```{r, eval=FALSE}

...

if (missing(col))

col <- getStockcol()

...

```

Hadley's tip: Invisibly returning the old value from

```{r, eval=FALSE}

setStockcol <- function(cols) {

prevcols <- getStockcol()

if (is.null(cols)) {

assign("stockcol", stockcol, envir = .pRolocEnv)

} else {

assign("stockcol", cols, envir = .pRolocEnv)

}

invisible(prevcols)

}

```

## Tidy data

> Hadley Wickham, Tidy Data, Vol. 59, Issue 10, Sep 2014, Journal of

> Statistical Software. http://www.jstatsoft.org/v59/i10.

Tidy datasets are easy to manipulate, model and visualize, and have a

specific structure: each variable is a column, each observation is a

row, and each type of observational unit is a table.

## Tidy tools

Tidy data also makes it easier to develop tidy tools for data

analysis, tools that both input and output tidy datasets.

- `dply::select` select columns

- `dlpy::filter` select rows

- `dplyr:mutate` create new columns

- `dpplyr:group_by` split-apply-combine

- `dlpyr:summarise` collapse each group into a single-row summary of

that group

- `magrittr::%>%` piping

## Examples

```{r, eval=FALSE}

library("dplyr")

surveys <- read.csv("http://datacarpentry.github.io/dc_zurich/data/portal_data_joined.csv")

head(surveys)

surveys %>%

filter(weight < 5) %>%

select(species_id, sex, weight)

surveys %>%

mutate(weight_kg = weight / 1000) %>%

filter(!is.na(weight)) %>%

head

surveys %>%

group_by(sex) %>%

tally()

surveys %>%

group_by(sex, species_id) %>%

summarize(mean_weight = mean(weight, na.rm = TRUE))

surveys %>%

group_by(sex, species_id) %>%

summarize(mean_weight = mean(weight, na.rm = TRUE),

min_weight = min(weight, na.rm = TRUE)) %>%

filter(!is.nan(mean_weight))

```

## Application to other data structures

> Hadley Wickham (@hadleywickham) tweeted at 8:45 pm on Fri, Feb 12,

> 2016: @mark_scheuerell @drob the importance of tidy data is not the

> specific form, but the consistency

> (https://twitter.com/hadleywickham/status/698246671629549568?s=09)

- Well-formatted and well-documented `S4` class

- `S4` as input -(function)-> `S4` as output

## Computing on the language

#### Quoting and evaluating expressions

Quote an expression, don't evaluate it:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

quote(1:10)

quote(paste(letters, LETTERS, sep = "-"))

```

Evaluate an expression in a specific environment:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

eval(quote(1 + 1))

eval(quote(1:10))

x <- 10

eval(quote(x + 1))

e <- new.env()

e$x <- 1

eval(quote(x + 1), env = e)

eval(quote(x), list(x = 30))

dfr <- data.frame(x = 1:10, y = LETTERS[1:10])

eval(quote(sum(x)), dfr)

```

Substitute any variables bound in `env`, but don't evaluate the

expression:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

x <- 10

substitute(sqrt(x))

e <- new.env()

e$x <- 1

substitute(sqrt(x), env = e)

```

Parse, but don't evaluate an expression:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

parse(text = "1:10")

parse(file = "lineprof-example.R")

```

Turn an unevaluated expressions into character strings:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

x <- 123

deparse(substitute(x))

```

#### Characters as variables names

```{r, eval=FALSE}

foo <- "bar"

as.name(foo)

string <- "1:10"

parse(text=string)

eval(parse(text=string))

```

And with `assign` and `get`

```{r, eval=FALSE}

varName1 <- "varName2"

assign(varName1, "123")

varName1

get(varName1)

varName2

```

Using `substitute` and `deparse`

```{r, eval=FALSE}

test <- function(x) {

y <- deparse(substitute(x))

print(y)

print(x)

}

var <- c("one","two","three")

test(var)

```