forked from murphyqm/key-data-vis-requirements

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 1

/

Copy pathapp.py

993 lines (756 loc) · 55.1 KB

/

app.py

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

624

625

626

627

628

629

630

631

632

633

634

635

636

637

638

639

640

641

642

643

644

645

646

647

648

649

650

651

652

653

654

655

656

657

658

659

660

661

662

663

664

665

666

667

668

669

670

671

672

673

674

675

676

677

678

679

680

681

682

683

684

685

686

687

688

689

690

691

692

693

694

695

696

697

698

699

700

701

702

703

704

705

706

707

708

709

710

711

712

713

714

715

716

717

718

719

720

721

722

723

724

725

726

727

728

729

730

731

732

733

734

735

736

737

738

739

740

741

742

743

744

745

746

747

748

749

750

751

752

753

754

755

756

757

758

759

760

761

762

763

764

765

766

767

768

769

770

771

772

773

774

775

776

777

778

779

780

781

782

783

784

785

786

787

788

789

790

791

792

793

794

795

796

797

798

799

800

801

802

803

804

805

806

807

808

809

810

811

812

813

814

815

816

817

818

819

820

821

822

823

824

825

826

827

828

829

830

831

832

833

834

835

836

837

838

839

840

841

842

843

844

845

846

847

848

849

850

851

852

853

854

855

856

857

858

859

860

861

862

863

864

865

866

867

868

869

870

871

872

873

874

875

876

877

878

879

880

881

882

883

884

885

886

887

888

889

890

891

892

893

894

895

896

897

898

899

900

901

902

903

904

905

906

907

908

909

910

911

912

913

914

915

916

917

918

919

920

921

922

923

924

925

926

927

928

929

930

931

932

933

934

935

936

937

938

939

940

941

942

943

944

945

946

947

948

949

950

951

952

953

954

955

956

957

958

959

960

961

962

963

964

965

966

967

968

969

970

971

972

973

974

975

976

977

978

979

980

981

982

983

984

985

986

987

988

989

990

991

992

993

import streamlit as st

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import plotly.express as px

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from matplotlib import colormaps

import matplotlib as mpl

import requests

import scipy as sp

import urllib.request

from PIL import Image

# from bokeh.plotting import figure

#from bokeh.transform import linear_cmap, factor_cmap

#from bokeh.palettes import Bokeh

@st.cache_data

def load_image_from_github(url):

img = np.array(Image.open(requests.get(url, stream=True).raw))

return img

my_pall ={'orange': '#e66101',

'pink': '#CA054D',

'blue': '#1B98E0',

'green':'#A4D4B4',

'purple': '#5e3c99', }

# data analysis

penguins = sns.load_dataset("penguins").dropna()

Penguins = penguins.rename(columns={"species": "Species",

"island": "Island",

"bill_length_mm": "Bill length (mm)",

"bill_depth_mm": "Bill depth (mm)",

"flipper_length_mm": "Flipper length (mm)",

"body_mass_g": "Body mass (g)",

"sex":"Sex"

})

# colour maps

# peng_cmap = factor_cmap(penguins, palette=Bokeh, factors=sorted(penguins.species.unique()))

# building data for ternary plot

locat = ["Locality #01B-32", "Locality #01B-34", "Locality #02C-01"]

local_no = np.random.choice(locat, 200)

local_var = np.zeros(200)

local_var [local_no == "Locality #01B-32"] = 1.3

local_var [local_no == "Locality #01B-34"] = -1.2

Qm_raw = 3.5 * np.random.randn(200) + 5

Qm_raw = Qm_raw + local_var

Qm_raw [Qm_raw <0] = 1.3

F_raw = 1.5 * np.random.randn(200) + 3

F_raw [F_raw <0] = 0.5

Lt_raw = 0.7 * np.random.randn(200) + 2

Lt_raw = Lt_raw - local_var

Lt_raw[Lt_raw <0] = 0.1

total_val = Qm_raw + F_raw + Lt_raw

norm_factor = 100/total_val

Qm = Qm_raw * norm_factor

F = F_raw * norm_factor

Lt = Lt_raw * norm_factor

geo_data = {"Qm":Qm,

"F":F,

"Lt":Lt,

"Locality Number": local_no}

geo_df = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(geo_data)

st.title('5 Concepts for Data Visualisation')

intro_text = """

This website introduces five key concepts to help you build better research data visualisations.

These are not the *only* rules, or the *only* way to approach building a robust and reproducible

graphical research output, but should help you to create visualisations in a methodical way.

"""

st.write(intro_text)

col1, col2 = st.columns(2)

pub_refs = """

# Sources and inspiration

A number of fantastic articles went into this resource. Please read these works: the content shared here is a much-abridged, simplified, shortened version of the content shared in the articles below.

#### Bibliography

Berinato, Scott. 2016. “Visualizations That Really Work.” Harvard Business Review, June 1, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/06/visualizations-that-really-work.

Franconeri, Steven L., Lace M. Padilla, Priti Shah, Jeffrey M. Zacks, and Jessica Hullman. 2021. “The Science of Visual Data Communication: What Works.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society 22 (3): 110–61.

Kelleher, Christa, and Thorsten Wagener. 2011. “Ten Guidelines for Effective Data Visualization in Scientific Publications.” Environmental Modelling & Software: With Environment Data News 26 (6): 822–27.

Midway, Stephen R. 2020. “Principles of Effective Data Visualization.” Patterns (New York, N.Y.) 1 (9): 100141.

Rougier, Nicolas P., Michael Droettboom, and Philip E. Bourne. 2014. “Ten Simple Rules for Better Figures.” PLoS Computational Biology 10 (9): e1003833.

#### Other resources

- [Berkeley Library Data Visualisation library guide](https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/data-visualization/about)

- [Tableau documentation: Visual Best Practices](https://help.tableau.com/current/blueprint/en-us/bp_visual_best_practices.htm)

- [from Data to Viz project](https://www.data-to-viz.com/)

- [Principles of Data Visualization workshop notes](https://ucdavisdatalab.github.io/workshop_data_viz_principles/)

- [What’s visual ‘encoding’ in data viz, and why is it important?](https://medium.com/@sophiewarnes/whats-visual-encoding-in-data-viz-and-why-is-it-important-7406bc88b4b4#:~:text=Encoding%20in%20data%20viz%20basically,trying%20to%20say%20or%20show.)

- [University of Utah visualization design lab](https://vdl.sci.utah.edu/)

"""

with col1:

with st.popover("Publications and references behind this tool"):

st.markdown(pub_refs)

package_references = """

#### matplotlib

J. D. Hunter, "Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment", Computing in Science & Engineering, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 90-95, 2007.

#### seaborn

Waskom, M. L., (2021). seaborn: statistical data visualization. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(60), 3021, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03021.

#### Plotly

Plotly Technologies Inc. Collaborative data science. Montréal, QC, 2015. https://plot.ly.

#### Streamlit

Streamlit documentation, https://docs.streamlit.io/

#### NumPy

Harris, C.R., Millman, K.J., van der Walt, S.J. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-020-2649-2.

### pandas

Data structures for statistical computing in python, McKinney, Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Volume 445, 2010.

"""

with col2:

with st.popover("Python packages and datasets used"):

st.header("Python packages")

st.markdown(package_references)

st.header("Datasets")

st.write("We use the `penguins` example dataset from the seaborn library. This can be browsed below:")

st.dataframe(penguins)

st.write("We also generated some random geological data to build a QFL ternary plot.")

st.dataframe(geo_df)

# st.markdown("""

# <style>

# .stTabs [data-baseweb="tab-list"] {

# gap: 2px;

# }

# .stTabs [data-baseweb="tab"] {

# height: 50px;

# white-space: pre-wrap;

# border-radius: 4px 4px 4px 4px;

# gap: 5px;

# padding-top: 10px;

# padding-bottom: 10px;

# font-size:4rem;

# }

# .stTabs [aria-selected="true"] {

# background-color: #FFFFFF;

# }

# </style>""", unsafe_allow_html=True)

tablist = [r"$\; \textsf{1.} \; \textsf{\Large Audience}\; \;$", r"$\; \textsf{2.} \; \textsf{\Large Story}\; \;$", r"$\; \textsf{3.} \; \textsf{\Large Encoding}\; \;$", r"$\; \textsf{4.} \; \textsf{\Large Composition}\; \;$", r"$\; \textsf{5.} \; \textsf{\Large Simplify}\; \;$"]

tab0, tab1, tab2, tab3, tab4 = st.tabs(tablist)

audience_gen = """

- Is the figure for yourself or direct collaborators? This may be the case if you are quickly checking if results are expected, are pulling together some notes for a supervisory or team meeting, or have some questions for a collaborator about some recent results.

- Is the figure for a scientific publication and so for a broader audience who has technical knowledge but does not know the details of your work specifically?

- Are you presenting a talk or a poster at a conference where the audience are mainly experts in your niche field?

- Is your audience going to be undergraduate students where the aim is to convey a concept or method with your data as an example, instead of conveying your results specifically?

- Is you data visualisation being used in an outreach setting for the general public without any assumed research or field-specific knowledge?

"""

md_0_a = """

Creating plots and graphs for yourself can be a fantastic way of quickly evaluating datasets, discovering patterns, and validating model output.

### Exploratory data visualisation

This is data visualisation with the intention of discovering something, as opposed

to displaying or proving something. The plots generated during the exploratory

or investigation stage will likely never make it into a publication or other

output: an awful lot of plots generated won't show anything interesting.

That's ok! That's the point! Because of this, generating these plots needs to

be rapid.

Exploratory data visualisation for yourself might be...

- Messy! Labels might be all lowercase, with underscores instead of spaces, and plots might use all default settings for colours.

- Informal

- Embedded in notebooks surrounded by exploratory notes

- Interactive

"""

domain_specific_plots = """

Certain research areas will have niche, domain-specific plots, that will be easily understandable by people within that field but would look unusual or confusing to someone outside. These sort of plots which require specialist knowledge can be very useful in quickly imparting detailed information. For example, the ternary plot below used for determining the provenance of sedimentary samples will be immediately recognised by those working in geology or a related field.

"""

general_research_audience = """

Some useful questions to ask include:

- What are common scientific/research terms, and what might be terms only understood by researchers in your specific field?

- What are some common assumptions in your field that might not be true of other domain areas, and will require explanation?

"""

gen_pop_info = """

Some useful questions to ask yourself include:

- Do we need to convey detailed number or can we focus instead on trends?

- How busy are our plots? Can we strip them down and split data up into different plots?

- How much information are we trying to deliver in each plot? Try to stick to one key message or piece of information.

"""

context_medium = """

- Is it going to be quickly viewed on a large projector screen as part of a presentation, with you talking over it?

- Possibly reveal features slowly, adding data as you explain

- Large font size and thick lines/large markers

- Should be rapidly digestible

- Your spoken word can act as a caption to explain the plot to the audience

- Will it be part of a published research article?

- Can expect people to spend a little longer reading it and absorbing the content

- Can include a lot of detail in the caption

- Will need to meet very specific dimension, font size and resolution specifications

- Will it be presented on a poster?

- Make it large enough to be comfortably read from a distance

- Be careful defining size and resolution to ensure it can be printed in large format

Depending on the context, you may need to play around with features such as transparency and colour palette to ensure your graphic is legible.

"""

context_part2 = """

#### Create the same plot for different contexts

The `seaborn` library allows you to change the setting of an argument called `"context"`. This automatically scales the line thickness, marker size and font size of your figure to better suit the presentation medium. You might still need to tweak these individually, but this is a quick way to update your plot.

"""

with tab0:

st.header("Why are you making a figure?")

st.markdown(audience_gen)

st.header("Who is your audience?")

with st.expander("a. Yourself!"):

st.markdown(md_0_a )

st.subheader("Interaction can aid exploration")

st.write("Interactivity is often not necessary outside of specific applications,",

"and can be overused to hide other issues with a visualisation (such as not knowing the message or story it is supposed to tell),",

"but in the case of exploratory data visualisation it's ok",

"not to know that the message or story is yet!")

st.write("Quickly-built interactive visualisations using libraries such as `plotly` or `bokeh` can be a useful step in figuring out whether your",

"plot should highlight the overall, large-scale patterns in the data,",

"or if it should zoom in on the details.")

st.scatter_chart(penguins, x="bill_length_mm", y="bill_depth_mm",

color="species", size="island")

st.write("*Caption: Adelie penguins resident on all three islands; others restricted to single island. Check if any correlation between Adelie stats and location...*")

st.write("Using size as a method of encoding unordered categorical data (as in the figure above) isn't best practise,",

"but it's ok to be a little sloppy when developing plots only for yourself.",

"This figure lets you explore the clustering of bill size with species,",

"but also shows the distribution of different species on different islands if you zoom in and hover over the data.",

"This plot wouldn't be the best way of showing either of those features, but it's useful to help us spot these trends.")

st.scatter_chart(penguins.loc[penguins['species'] == "Adelie"], x="flipper_length_mm", y="body_mass_g",

color="island",)

st.write("*Caption: no obvious correlation between physical characteristics and location; can do some exploratory stats.*")

st.subheader("Captions")

st.write("Captions do not have to be as formal when building an exploratory plot for yourself; however it's still useful to tag any figures with your notes. This could be by adding some markdown text in a Jupyter notebook after the figure (shown above in italics), or by adding info to the title. It's easy to forget what info you have gleaned from a particular plot, and noting it down like this can help save you time repeating yourself.")

with st.expander("b. Your research group or collaborators"):

st.subheader("Informality depends on context")

st.write("For quick meetings, exploratory plots without much formatting might be sufficient;",

"however, bear in mind whether you are meeting in-person to talk through the plot",

"or whether the work needs to be able to stand on its own alongside an explanatory note.")

st.write("While the plots might still be somewhat exploratory, and you may want to maintain some interaction for discussion, it's likely you'll want to have a better idea of the message or key result behind the plot. We'll discuss this more in **Section 2: Story**")

st.write("While in a publication, you would pick one plot that best highlights a particular pattern or feature, when putting together figures for discussion it can be useful to provide a few different but similar views to help discover the most useful way of presenting the data.")

fig = px.histogram(penguins, x="bill_length_mm", y="bill_depth_mm",

color="species",marginal="box")

st.plotly_chart(fig, use_container_width=True)

fig2 = px.scatter(penguins, x="bill_length_mm", y="bill_depth_mm",

color="species", marginal_y="violin", marginal_x="box",

trendline="ols", )

st.plotly_chart(fig2, use_container_width=True,)

st.subheader("Captions")

st.write("Again, captions are really useful for giving your collaborators a peek inside your thought process.",

"They can be conversational and open ended, but should convey what message you think might be lurking in the data.")

with st.expander("c. Specialists in your domain"):

st.subheader("Domain-specific plots")

st.markdown(domain_specific_plots)

fig5 = px.scatter_ternary(geo_df, a="Qm", b="F", c="Lt", color="Locality Number")

st.plotly_chart(fig5, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("*Caption: Quartz, feldspar and lithic fragments (QFL) ternary plot for sedimentary samples returned from three localities (locality number listed in legend, denoted by colour). Quartz, feldspar and lithic fragments have been point counted in thin section and normalised to 100 %. Please see the main text for a discussion of location in QFL space and likely provenance of samples in each location.*")

st.subheader("Captions")

st.write("Captions should be detailed and define every piece of visual information in the figure. A non-specialist should still be able to determine the main message of your plot after reading the caption, even if the layout of the plot is new to them.")

with st.expander("d. Researchers outside your domain"):

st.write("A more general research audience may require more hand-holding to digest niche or complex plots. This can be done by reducing the amount of information being conveyed in the plot, by incorporating helpful labels, or by creating multiple panels and splitting up the data.")

st.markdown(general_research_audience)

with st.expander("f. General public"):

st.write("More illustrative or infographic-style plots are often popular",

"when designing data visualisation for the general public;",

"however, more quant-style plots are also often needed.",

"In general, it is useful to label your data clearly and avoid",

"unexplained scientific jargon—this is true of **all** data vis,",

"but becomes especially necessary when presenting to non-technical audiences.")

st.write("In general, all the follow-on rules and guidelines we discuss in later sections are more important for figures created for the general public: other, more specialist audiences will be more forgiving of bad design choices as they have been trained to read scientific visualisations.")

st.markdown(gen_pop_info)

fig3 = px.scatter(penguins, x="bill_length_mm", y="bill_depth_mm",

color="species",hover_data=['sex', "island"],

title="Different penguin species have differently shaped bills",

labels={

"bill_length_mm": "Bill length (mm)",

"bill_depth_mm": "Bill depth (mm)",

"species": "Penguin Species",

"island": "Location (island name)",

"sex": "Sex"

})

fig3.add_annotation(text="Stubby, short, deep bills", x=35, y=21.55, showarrow=False)

fig3.add_annotation(text="Slender, long, shallow bills", x=54, y=13.5, showarrow=False)

fig3.add_annotation(text="Large, long, deep bills", x=54, y=21.55, showarrow=False)

st.plotly_chart(fig3, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("*Caption: the shape (or aspect ratio) of a penguins bill (the bill depth times and bill length) is related to the species of penguin. You can see the three distinct clusters of aspect ratio, and how this correlates with species. Click on the species name in the legend to toggle if its included in the plot.*")

st.write("Descriptive titles carrying the main message of the plot can be very useful in highlighting the story being told by the data.",

"Captions can expand on this further.",

"Text annotations can provide additional context. In the example above, a cartoon diagram of each bill morphology could be added in place of the text annotations.")

fig4 = px.scatter(penguins, x="flipper_length_mm", y="body_mass_g",

hover_data=["species", "island", "sex"],

title="Different penguin species have differently shaped bills",

labels={

"flipper_length_mm": "Flipper length (mm)",

"body_mass_g": "Body mass (g)",

"species": "Penguin Species",

"island": "Location (island name)",

"sex": "Sex"

},

trendline="ols",)

st.plotly_chart(fig4, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("*Caption: there is a relationship between penguin body mass and flipper length: heavier penguins are likely to have longer flippers; however, the relationship is not perfect with a lot of variation.*")

st.header("What's the context and the medium?")

with st.expander("Where will your visualisation be shown?"):

st.markdown(context_medium)

if "context" not in st.session_state:

st.session_state.context = "paper"

st.session_state.palette = "Set2"

st.session_state.alpha = 0.7

with st.expander("Different versions of the same plot"):

st.markdown(context_part2)

col1, col2, col3 = st.columns(3)

with col1:

st.radio(

'Pick a plot `"context"`: ',

key="context",

options=["paper", "talk", "poster"]

)

with col2:

st.radio(

"Pick a colour palette: ",

key="palette",

options=["Set2", "pastel", "colorblind"]

)

with col3:

st.radio(

"Pick a marker transparency:",

key="alpha",

options=[1, 0.7, 0.5]

)

fig6 = plt.figure()

with sns.axes_style("ticks"):

sns.set_context(st.session_state.context)

sns.set_palette(st.session_state.palette)

ax = sns.scatterplot(data=Penguins, x="Body mass (g)", y="Flipper length (mm)", hue="Island", style="Sex", alpha=st.session_state.alpha)

sns.despine()

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1))

st.pyplot(fig6, use_container_width=True,)

story_01 = """

A figure can express an idea quickly, succinctly, and straightforwardly. However, it is important to know exactly what the message of the figure is, to avoid creating either pointless plots that don’t really tell much, or overly complex plots that try to tell far too much.

#### Diagram first

Try sketching out some ideas with pen and paper to explore how you might want to present the data. Exploratory data vis (discussed in the previous slide) is also useful for this.

- What's the result you want to showcase? Can you explain it in a single sentence?

- Do you need to show the **broad trends** or the **fine-grained details** to tell the story?

- These should usually be separated; if both are relevant, split them into two separate plots

- What is the **simplest graph possible** that will communicate the meaning?

#### Collaborate and share

Share your plots from an early stage (perhaps even at the sketching-with-pen-and-paper stage) to see if your peers can quickly grasp the message you are hoping to convey.

>You know your data and your research very well; the patterns you are trying to highlight might be very obvious to you when you look at your figure, but completely hidden to someone looking at it for the first time.

#### What sort of plots are even out there?

When trying to figure out what kind of plot wll best help to visualise your message, it's useful to remind yourself of what kind of plots even exist!

"""

plot_inspiration = """

#### Plotting library galleries and showcases

A great place to find out whats available and what you can achieve is to scroll through some of the well-curated example galleries and tutorials published alongside many of the popular Python plotting libraries.

Some notable examples include:

- [Example gallery: seaborn](https://seaborn.pydata.org/examples/index.html)

- [Plotly documentation](https://plotly.com/python/)

- [Bokeh gallery: Topic guide](https://docs.bokeh.org/en/latest/docs/gallery.html)

There are also some larger-scale collected galleries that include multiple libraries:

- [The Python Graph Gallery](https://python-graph-gallery.com/)

- This gallery breaks up plots from a range of different libraries into topics such as distribution, correlation, ranking, evolution, and mapping

#### Articles on data visualisation

While not specifically sharing Python libraries, general articles discussing great data visualisation can be a useful place to discover new kinds of plots and to inspire yourself; these sorts of posts can often be found on [company blogs](https://visme.co/blog/best-data-visualizations/)

#### Research articles

When keeping up-to-date on research in your field, make sure to save any impressive figures that you want to draw inspiration from at a later point!

Some of the high-budget, flashier journals often have impressive graphics in their featured articles (for example, [Nature](https://www.nature.com/subjects/astronomy-and-astrophysics)). Look outside of your research area to discover new ways of plotting.

"""

types_of_plot = """

- [From Data to Viz](https://www.data-to-viz.com/): a flowchart to help you find the most suitable plot for your data

- [The Data Visualisation Catalogue](https://datavizcatalogue.com/): a non-code-based library of different information visualisation types

- [Tableau documentation: Chart choice](https://help.tableau.com/current/blueprint/en-us/bp_visual_best_practices.htm#chart-choice)

"""

with tab1:

st.markdown(story_01)

with st.expander("Basic plot types"):

st.markdown(types_of_plot)

with st.expander("Finding plot inspiration"):

st.markdown(plot_inspiration)

encoding_01 = """

When discussing data visualisation, **data encoding** essentially means *how you translate the data into a visual element on a chart* ([Warnes, 2018](https://medium.com/@sophiewarnes/whats-visual-encoding-in-data-viz-and-why-is-it-important-7406bc88b4b4#:~:text=Encoding%20in%20data%20viz%20basically,trying%20to%20say%20or%20show.)). In her fantastic blog post, [Sophie Warnes](https://medium.com/@sophiewarnes/whats-visual-encoding-in-data-viz-and-why-is-it-important-7406bc88b4b4#:~:text=Encoding%20in%20data%20viz%20basically,trying%20to%20say%20or%20show.) describes data encoding as a set of rules to follow, giving the following logic:

> *Every time <data changes in some way>, do <something visual>,*

where the *something visual* is the encoding.

Starting simply, lets consider a scatter plot. We can think about how we might change a point marker to encode the data. There are many different ways we can encode data in this setting, including but not limited to:

- **Position**

- The *x* and *y* co-ordinates reflect the data

- **Colour**

- Colour can be used to represent a continuous numerical value (colour map)

- Colour can be used to represent discrete or categorical data

- **Shape**

- Marker shape could be used to represent categorical data or highlight specific points

- **Size**

- Size could be used to represent a continuous numerical value or category

> How many distinct values do you need to discriminate between? This can define the method of encoding that best suits your needs.

We're going to look at two main factors as we discuss encoding data:

##### 1. Truthful and non-misleading graphics

##### 2. Easy to read, efficient graphics

---

Take some time to read through the UCDavis DataLab [Principles of Visual Perception](https://ucdavisdatalab.github.io/workshop_data_viz_principles/principles-of-visual-perception.html) section in their data visualisation workshop notes.

They highlight a number of ways we can be misled by graphics, and how we can leverage the way our brains absorb visual information to build better data visualisations. For example, see the figure below:

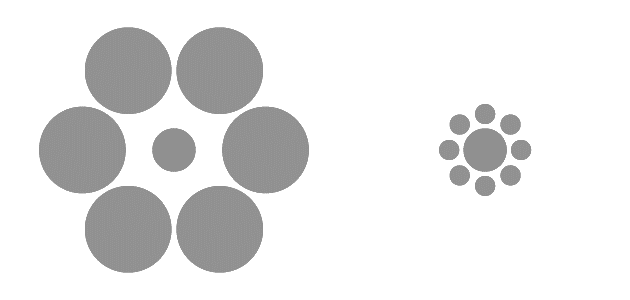

*Caption: Which inner circle is bigger? From [UCDavis Principles of data Visualisation workshop](https://ucdavisdatalab.github.io/workshop_data_viz_principles/principles-of-visual-perception.html#visual-magic-tricks)*

---

## 1. Building truthful and non-misleading graphics

> How effective are the different methods of encoding data shown below? What are some limitations or drawbacks of each option?

"""

encoding_02 = """

## 2. Building easy to read, efficient graphics

We want people to be able to quickly absorb information from our plots. Research generally handles complex topics, and the visualisations that we build are often trying to distil the results of months or years of complex work. We want our audience to simultaneously scan our figure, read labels and annotations, and absorb the salient points. This is a lot to juggle, and it's in our best interests to reduce the cognitive load and the strain on the visual working memory of our reader.

Thankfully, there's a whole host of research on how to best create visualisations that allow the audience to quickly absorb information and to leverage intuitive shortcuts to make our plots more digestible.

#### Pre-attentive attributes

The [Tableau documentation](https://help.tableau.com/current/blueprint/en-us/bp_why_visual_analytics.htm) defines pre-attentive attributes as **"information we can process visually almost immediately"**, without thinking.

These attributes include [length, width, orientation, size, shape, enclosure, position, grouping, colour hue, and colour intensity](https://help.tableau.com/current/blueprint/en-us/Img/bp_why_visual_analytics.png). Leveraging these encoding channels can help to make your visualisation more rapidly understandable.

These attributes can be ranked according to the accuracy with which we can estimate their value: position and length are usually accurately estimated by the viewer (with sensible axes labels, scales, placement etc.), followed by angle and slope, then area, volume, colour, and density/saturation ([Mackinlay, 1986](https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/22949.22950); [UCDavis DataLab](https://ucdavisdatalab.github.io/workshop_data_viz_principles/principles-of-visual-perception.html#perception-and-encodings)).

#### Gestalt principles of grouping

As well as looking at the effect of the individual encoding of datapoints, we need to consider the plot as a whole. Gestalt psychology looks at how people perceive things as a whole entity rather than as separate parts. Without the time to dive into the backgroiund of this field of psychology and address some of the assumptions and caveats (see [Table 2, Wagemans et al., 2012](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482144/)), lets briefly look at some of the principles of grouping that can be applied to your figure making.

- **Proximity**

- How near to each other objects are

- Our brain performs automatic clustering of points, and considers items close to each other as related

- This can be used...

- When arranging plots in a facet layout or a grid

- When arranging 1D plots such as bar charts

- When creating visualisations without numeric values on the *x* or *y* axes

- **Similarity**

- How similar objects are to each other

- Using the encoding channels explained above for marker style to group points

- Use [this graphic](https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-data-visualizations/9781449314774/ch04.html#use_this_table_of_common_visual_properti) to pick an appropriate channel for the number of discrete values/groups you need to identify

- **Connection**

- Whether data points are isolated or connected

- Points that are connected to each other (via a line) are perceived as related

- Line style, colour and opacity can be varied

- **Enclosure**

- Whether points are encircled in a group or have a different background colour/shading in a region

- Points enclosed in a region are perceived as related

- Annotations can be added to enclosed regions

For further information, please see [UCDavis DataLab Principles of Data Visualisation notes](https://ucdavisdatalab.github.io/workshop_data_viz_principles/principles-of-visual-perception.html#gestalt-principles), [Wagemans et al., 2012](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3482144/), and [Peterson and Berryhill, 2013](https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-013-0460-x)

"""

encoding_refs = """

**References**

Berinato, Scott. 2016. “Visualizations That Really Work.” Harvard Business Review, June 1, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/06/visualizations-that-really-work.

Franconeri, Steven L., Lace M. Padilla, Priti Shah, Jeffrey M. Zacks, and Jessica Hullman. 2021. “The Science of Visual Data Communication: What Works.” Psychological Science in the Public Interest: A Journal of the American Psychological Society 22 (3): 110–61.

Kelleher, Christa, and Thorsten Wagener. 2011. “Ten Guidelines for Effective Data Visualization in Scientific Publications.” Environmental Modelling & Software: With Environment Data News 26 (6): 822–27.

Wagemans, Johan, James H. Elder, Michael Kubovy, Stephen E. Palmer, Mary A. Peterson, Manish Singh, and Rüdiger von der Heydt. 2012. “A Century of Gestalt Psychology in Visual Perception: I. Perceptual Grouping and Figure-Ground Organization.” Psychological Bulletin 138 (6): 1172–1217.

"""

colour_choice = """

Some things to keep in mind when picking a colour palette for your figure:

1. Is the data ordered or not? Do you need to use a **qualitative**, **sequential** or **diverging** palette?

2. How many levels need to be distinguishable?

3. Will the plot be readable if you have a colour vision deficiency (i.e., colour blindness)?

4. Will the plot be readable if printed in black and white?

5. Is there enough contrast between the different colours that it will be legible on a range of different screens?

You can avail of tools such as [ColorBrewer](https://colorbrewer2.org/) to pick a basic scientific palette. For more fine-grained control, try using [Chroma.js](https://gka.github.io/palettes/#/9|s|00429d,96ffea,ffffe0|ffffe0,ff005e,93003a|1|1) or [Colorgorical](http://vrl.cs.brown.edu/color) to generate palettes.

If you already have a palette in mind, test it out with the fantastic [Viz Palette](https://projects.susielu.com/viz-palette) tool. This will allow you to export hex codes of colours to use in Python.

Further reading:

- [Your Friendly Guide to Colors in Data Visualisation](https://blog.datawrapper.de/colorguide/)

- [Best Color Palettes for Scientific Figures and Data Visualizations](https://www.simplifiedsciencepublishing.com/resources/best-color-palettes-for-scientific-figures-and-data-visualizations#:~:text=How%20to%20Find%20the%20Best,and%20other%20color%20perception%20difficulties.)

"""

heatmaps_md = """

There is a wealth of information and research into choosing the best heatmap to illustrate your data.

[Crameri et al. (2020)](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-19160-7) highlight some of the issues with using poorly designed heatmaps:

> Zones of danger, such as the boundaries of a hurricane track or current virus spread, are often based on uneven colour gradients to accentuate their importance. [...] Decisions based on data being ‘unfairly’ represented could produce, for instance, a Martian rover being sent over terrain that is too steep as the topography was inaccurately visualised, or a medical worker making an incomplete or inaccurate diagnosis based on uneven colour gradients.

- You can see in the examples above how the `spring` heatmap squashes details at the extremes of the data, so you lose information near the max and minimum values.

- While `jet` allows us to see detail in the extremes of the data, it also produces artifacts due to jumps in lightness between colours.

- The `plasma` colourmap removes these jump artifacts, and allows us to see more in the extreme values than `spring` did.

- The `turbo` colourmap has been designed as a replacement for [`jet`](https://research.google/blog/turbo-an-improved-rainbow-colormap-for-visualization/), where "where perceptual uniformity is not critical, but one still wants a high contrast, smooth visualization of the underlying data". This allows maxima and minima to be clearly seen, and doesn't produce artifical large jumps in brightness.

See the [matplotlib documentation on colour maps for examples](https://matplotlib.org/stable/users/explain/colors/colormaps.html#lightness-of-matplotlib-colormaps).

Other heatmap tools for Python include ["batlow": the Scientific colour map](https://www.fabiocrameri.ch/batlow/), [seaborn colour maps](https://seaborn.pydata.org/tutorial/color_palettes.html#sequential-color-palettes), [cmocean colour maps](https://matplotlib.org/cmocean/), [the SciCoMap package](https://github.com/ThomasBury/scicomap) and the related [blog pot](https://towardsdatascience.com/your-colour-map-is-bad-heres-how-to-fix-it-lessons-learnt-from-the-event-horizon-telescope-b82523f09469)

"""

cmaps = {}

gradient = np.linspace(0, 1, 256)

gradient = np.vstack((gradient, gradient))

def plot_color_gradients(category, cmap_list):

# Create figure and adjust figure height to number of colormaps

nrows = len(cmap_list)

figh = 0.35 + 0.15 + (nrows + (nrows - 1) * 0.1) * 0.22

fig, axs = plt.subplots(nrows=nrows + 1, figsize=(6.4, figh))

fig.subplots_adjust(top=1 - 0.35 / figh, bottom=0.15 / figh,

left=0.2, right=0.99)

axs[0].set_title(f'{category} colormaps', fontsize=14)

for ax, name in zip(axs, cmap_list):

ax.imshow(gradient, aspect='auto', cmap=mpl.colormaps[name])

ax.text(-0.01, 0.5, name, va='center', ha='right', fontsize=10,

transform=ax.transAxes)

# Turn off *all* ticks & spines, not just the ones with colormaps.

for ax in axs:

ax.set_axis_off()

# Save colormap list for later.

cmaps[category] = cmap_list

return fig

with tab2:

st.markdown(encoding_01)

with st.expander("Compare different encoding methods"):

if "encoding" not in st.session_state:

st.session_state.encoding = "All the above"

st.radio("Pick an *encoding channel*:", key="encoding",

options=["Marker shape", "Marker colour", "Marker size", "All the above"])

args_full = {"style":"Island", "hue":"Island", "size":"Island"}

args_style = {"style":"Island"}

args_hue = {"hue":"Island"}

args_size = {"size":"Island"}

if st.session_state.encoding == "All the above":

args_ = args_full

elif st.session_state.encoding == "Marker shape":

args_ = args_style

elif st.session_state.encoding == "Marker colour":

args_ = args_hue

elif st.session_state.encoding == "Marker size":

args_ = args_size

else:

args_ = args_full

fig7 = plt.figure()

with sns.axes_style("ticks"):

sns.set_context("talk")

sns.set_palette("Set2")

ax = sns.scatterplot(data=Penguins, x="Body mass (g)", y="Flipper length (mm)", alpha=0.9, **args_ )

sns.despine()

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1), title="Encoding")

st.pyplot(fig7, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("Refer to [this useful graphic](https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-data-visualizations/9781449314774/ch04.html#use_this_table_of_common_visual_properti) when trying to decide what encoding channel to use.")

with st.expander("Size of marker as an encoding channel..."):

st.write("Size is an attribute that is easy to set to map onto a numerical value, to provide a third dimension to your visualisation.",

"However, there are a few issues with this approach.")

st.subheader("1. We are not very good at estimating area")

st.write("It's difficult to accurately estimate the area of a marker, making it difficult for readers to decode our visualisation. This is also why it's best to [avoid pie-charts wherever possible](https://theconversation.com/heres-why-you-should-almost-never-use-a-pie-chart-for-your-data-214576#:~:text=Pie%20charts%20also%20do%20badly,of%20categories%20in%20one%20pie.&text=The%20tiny%20slices%2C%20lack%20of,make%20interpretation%20difficult%20for%20anyone.)")

st.subheader("2. It's not always clear or obvious the component of 'size' that maps onto the value, or how it scales")

st.write("Different Python plotting libraries tie different marker attributes to the idea of 'size' - marker diameter, radius, and area. This means that different marker shapes masy scale differently for different packages.")

st.write("Then depending on the scale of your data, you may have to use a multiple or factor to adjust the size relationship to make it visible in your plot. See below for the different effects this can have.")

x = [0,2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16,18]

s_exp = [20*2**n for n in range(len(x))]

s_square = [20*n**2 for n in range(len(x))]

s_linear = [20*n for n in range(len(x))]

fig_05, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.scatter(x,[1]*len(x),s=s_exp, label='$s=20 * 2^x$', lw=1, alpha=0.6, c=my_pall["pink"])

ax.scatter(x,[0]*len(x),s=s_square, label='$s=20 * x^2$', alpha=0.7, c=my_pall["blue"])

ax.scatter(x,[-1]*len(x),s=s_linear, label='$s=20 * x$', alpha=0.7, c=my_pall["orange"])

for i in x:

ax.text(i, -1.6, str(i), horizontalalignment='center', verticalalignment='center')

ax.axes.vlines(x=22, ymin=-1.7, ymax=1.6, colors="grey", linestyles=":", linewidths=2)

ax.set_ylim(-2,2)

ax.set_xlim(-0.5, 22)

ax.set_xlabel("X")

ax.legend(loc='center left', bbox_to_anchor=(1.05, 0.45), labelspacing=6, frameon=False, handletextpad=3.5)

ax.spines[:].set_visible(False)

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_xticks([])

st.pyplot(fig_05, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("*Caption: Size (s) in matplotlib library set as different mutliples of x value.*")

st.subheader("Implying order")

with st.expander("How might data encoding imply that the data is ordered?"):

st.write("Both these figures use the same randomly generated data.",

"What inferences might you draw from each of these plots? How is this effected by the encoding of the data?")

# Create a figure and axes, and set the figure size in inches

col_a, col_b = st.columns(2)

with col_a:

fig8, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7, 4))

# Random data

x = np.random.randn(50) + 2

y = np.random.randn(50) - 1

x1 = np.random.randn(50)

y1 = np.random.randn(50)

x2 = np.random.randn(50) - 2

y2 = np.random.randn(50) - 1

x3 = np.random.randn(50) + 2

y3 = np.random.randn(50) + 2

# Plot the data as a scatter plot

ax.scatter(x, y, label="Group A", c=my_pall["pink"], alpha=0.5, marker="*", s=130)

ax.scatter(x1, y1, label="Group B", c=my_pall["blue"], alpha=0.5, marker="X", s=130)

ax.scatter(x2, y2, label = "Group C", c=my_pall["orange"], alpha=0.5, s=120)

ax.scatter(x3, y3, label = "Group D", c=my_pall["purple"], alpha=0.5, s=110, marker="s")

# Set title and labels

ax.legend()

ax.set_title('Scatter Plot')

ax.set_xlabel('X')

ax.set_ylabel('Y')

ax.spines[["top", "right"]].set_visible(False)

st.pyplot(fig8, use_container_width=True,)

with col_b:

fig9, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7, 4))

new_pall = ["#cbc9e2",

"#9e9ac8",

"#756bb1",

"#54278f",]

# Plot the data as a scatter plot

ax.scatter(x, y, label="Group A", c=new_pall[0], alpha=0.8, s=200)

ax.scatter(x1, y1, label="Group B", c=new_pall[1], alpha=0.8, s=150)

ax.scatter(x2, y2, label = "Group C", c=new_pall[2], alpha=0.8, s=100)

ax.scatter(x3, y3, label = "Group D", c=new_pall[3], alpha=0.8, s=50, )

# Set title and labels

ax.legend()

ax.set_title('Scatter Plot')

ax.set_xlabel('X')

ax.set_ylabel('Y')

ax.spines[["top", "right"]].set_visible(False)

st.pyplot(fig9, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("*Caption: Randomly generated data using different shape, size and colour encoding.*")

st.write("Order can be implied by colour, size, position, angle (of marker). Ensure that you do not unintentionally imply that data are ordered when they are not.",

"When listing data sets in the legend, if there is no scientific basis for ordering them in a specific way, alphabetise them, so as not to unintentionally apply a ranking. For example, country names should be alphabetised inside alphabetised continent headers.")

with st.expander("Colour always means something"):

st.write("Be mindful when selecting colours for your plots.",

"It's good to keep in mind what colour might represent to your audience, and if this is what you intended.",

"For example, when building a plot discussing political party results,",

"the colours red and blue will have different meanings and interpretation depending on the country.",

"Similarly, using a continuous colour map, or varying saturation and intensity can imply that the data is ordered, as in the above example.")

st.markdown(colour_choice)

st.subheader("Implying contrast")

st.write("Colour, markersize, location, opacity/saturation and labels can be used to emphasise contrast. Later in the course, we will also discuss how axes scaling can be used to artifically increase contrast between datapoints.")

st.write("Unintentional emphasis on contrast can most easily creep in when using continuous colour maps to illustrate data.")

with st.popover("Compare different colour maps (N.B. this will stay open as you scroll)"):

if "heatmap" not in st.session_state:

st.session_state.heatmap = "plasma"

if "ex_image" not in st.session_state:

st.session_state.ex_image = "https://www.leeds.ac.uk/images/resized/1200x600-0-0-1-80-ParkinsonBuilding_2.jpg"

st.radio("Choose a matplotlib heatmap:",key="heatmap",

options=["plasma","jet","turbo","spring"])

jpg_image =load_image_from_github("https://astropedia.astrogeology.usgs.gov/download/Mars/GlobalSurveyor/MOLA/thumbs/Mars_MGS_MOLA_DEM_mosaic_global_1024.jpg)")

image = jpg_image[:,:,0]

image = ((21229+8200)*(image/255)) - 8200

fig, ax = plt.subplots(layout='constrained')

with sns.axes_style("ticks"):

sns.set_context("paper")

im = ax.imshow(image, cmap=st.session_state.heatmap, extent=[-180, 180, -90, 90])

fig.colorbar(im, orientation="horizontal", label="Elevation relative to areoid [M]")

ax.set_xlabel("Longitude")

ax.set_ylabel("Latitude")

st.pyplot(fig, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("Sometimes this is more easily seen with a photograph. Enter your photograph url below.")

ex_im = st.text_input("image URL", "https://www.leeds.ac.uk/images/resized/1200x600-0-0-1-80-ParkinsonBuilding_2.jpg")

new_im = load_image_from_github(str(ex_im))

image = new_im[:,:,0]

image = ((21229+8200)*(image/255)) - 8200

fig_new, ax = plt.subplots(layout='constrained')

with sns.axes_style("white"):

sns.set_context("paper")

im = ax.imshow(image, cmap=st.session_state.heatmap)

ax.set(xticklabels=[], yticklabels=[])

ax.tick_params(left=False,bottom=False)

sns.despine(left=True, bottom=True)

st.pyplot(fig_new, use_container_width=True,)

with st.expander("Picking heatmaps"):

st.write(heatmaps_md)

st.markdown(encoding_02)

st.divider()

st.markdown(encoding_refs)

comp_01 = """

"""

with tab3:

st.write("We've looked at the data points in your plot. Now lets look at the box around those points: everything besides the data!")

fig10, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(7, 4))

# Set title and labels

ax.set_title('Scatter Plot')

ax.set_xlabel('X')

ax.set_ylabel('Y')

st.pyplot(fig10, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("*Caption: An empty Figure and axes object with no points plotted.*")

def loguniform(low=0, high=1, size=None):

return np.exp(np.random.uniform(low, high, size))

# Random data

x = np.random.randn(50) + 2

y = np.random.randn(50) - 1

x1 = np.random.randn(50)

y1 = np.random.randn(50)

x2 = np.random.randn(50) - 2

y2 = np.random.randn(50) - 1

x3 = np.random.randn(50) + 2

y3 = np.random.randn(50) + 2

x3l = loguniform(low=0, high=5, size=50)

y3l = loguniform(low=0, high=5, size=50)

with st.expander("Axes labels"):

st.write("Ensure your figure axes are labelled and include units if relevant (almost always will be!)")

with st.expander("Axes scale"):

st.write("Choose a sensible scale for your dataset. This can include usin a log scale, or changing the limits (maximum and minimum values) of the axes.")

x_scale = st.radio("X axes scale", options=["linear", "log"])

y_scale = st.radio("Y axes scale", options=["linear", "log"])

fig_01, axs= plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(7, 4))

# Plot the data as a scatter plot

axs[0].scatter(x, y, label="Group A", c=my_pall["pink"], alpha=0.5, marker="*", s=130)

axs[0].scatter(x1, y1, label="Group B", c=my_pall["blue"], alpha=0.5, marker="X", s=130)

axs[0].scatter(x2, y2, label = "Group C", c=my_pall["orange"], alpha=0.5, s=120)

axs[0].scatter(x3l, y3l, label = "Weird", c=my_pall["purple"], alpha=0.5, s=110, marker="s")

# Set title and labels

axs[0].set_title('Scatter Plot 1')

axs[0].set_xlabel('X')

axs[0].set_ylabel('Y')

axs[0].spines[["top", "right"]].set_visible(False)

axs[1].scatter(x, y, label="Group A", c=my_pall["pink"], alpha=0.5, marker="*", s=130)

axs[1].scatter(x1, y1, label="Group B", c=my_pall["blue"], alpha=0.5, marker="X", s=130)

axs[1].scatter(x2, y2, label = "Group C", c=my_pall["orange"], alpha=0.5, s=120)

axs[1].scatter(x3, y3, label = "Weird", c=my_pall["purple"], alpha=0.5, s=110, marker="s")

# Set title and labels

axs[1].set_title('Scatter Plot 2')

axs[1].set_xlabel('X')

axs[1].set_ylabel('Y')

axs[1].spines[["top", "right"]].set_visible(False)

axs[0].set_yscale(y_scale)

axs[0].set_xscale(x_scale)

axs[1].set_yscale(y_scale)

axs[1].set_xscale(x_scale)

st.pyplot(fig_01, use_container_width=True,)

with st.expander("Placing the legend"):

st.write("In some of the examples with randomly generated data, you'll see that the Python library being used attempts to find the best location for the legend, where it overlaps the least number of points.",

"It is a good idea to move the legend outside of the plot area and to one side in these situations.")

with sns.axes_style("ticks"):

sns.set_context("talk")

sns.set_palette("Set2")

ax = sns.scatterplot(data=Penguins, x="Body mass (g)", y="Flipper length (mm)", alpha=0.9, **args_full )

sns.despine()

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1), title="Legend outside")

st.pyplot(fig7, use_container_width=True,)

with st.expander("Multiple panels"):

st.write("It can be helpful to split your plots into multiple panels to make it easier for your readers to absorb complex data.")

with sns.axes_style("ticks"):

sns.set_context("notebook")

sns.set_palette("Set2")

fig_02 = sns.relplot(data=Penguins, x="Body mass (g)", y="Flipper length (mm)", alpha=0.9, hue="Island", style="Sex")

sns.despine()

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1),)

st.pyplot(fig_02, use_container_width=True,)

with sns.axes_style("ticks"):

sns.set_context("talk")

sns.set_palette("Set2")

fig_03 = sns.relplot(data=Penguins, x="Body mass (g)", y="Flipper length (mm)", alpha=0.9, hue="Island", style="Island",col="Sex")

sns.despine()

sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1),)

st.pyplot(fig_03, use_container_width=True,)

st.write("Align the axes you want to compare: stack plots vertically if you want to ocmpare the x axes; place them side by side if you want to focus on the y axes.")

simplify_01 = """

The simpler your plot the better.

### Use the simplest and most basic plot possible to tell your story

A lot of visual clutter and plot complexity comes from not having a solid idea of the message of the plot before you start plotting, and attempting to fit too much in.

### Remove clutter whenever possible

**If your plot is confusing, try to clarify it by removing something, not adding extra labels and annotations.** Beware of chartjunk, like filled backgrounds and uneccessary grids.

"""

with tab4:

st.markdown(simplify_01)

with sns.axes_style("darkgrid"):

sns.set_context("notebook")

sns.set_palette("Set2")

fig_02 = sns.lmplot(data=Penguins, x="Body mass (g)", y="Flipper length (mm)", hue="Island", markers=["o", "x", "*"])

# sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1),)

st.pyplot(fig_02, use_container_width=True,)

st.divider()

st.write("Sometimes this can be as simple as removing grid lines.")

with sns.axes_style("ticks"):

sns.set_context("notebook")

sns.set_palette("Set2")

fig_02 = sns.lmplot(data=Penguins, x="Body mass (g)", y="Flipper length (mm)", hue="Island", markers=["o", "x", "*"])

# sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1),)

st.pyplot(fig_02, use_container_width=True,)

st.divider()

st.write("Sometimes, it means splitting your plot into multiple panels and making each panel more simple. Don't pick a complicated and unusual statistical plot just because it looks interesting: does it actually serve the dataset and the message or result you want to convey? Might it confuse or mislead the reader?",

"Similar questions should be asked before building interactive or 3D visualisations. Does this actually help the reader to understand the message?")

def annotate(data, **kws):

r, p = sp.stats.pearsonr(data['Body mass (g)'], data['Flipper length (mm)'])

ax = plt.gca()

ax.text(.05, .8, 'r={:.2f}, p={:.2g}'.format(r, p),

transform=ax.transAxes)

with sns.axes_style("ticks"):

sns.set_context("talk")

sns.set_palette("Set2")

fig_03 = sns.lmplot(data=Penguins, x="Body mass (g)", y="Flipper length (mm)", col="Island", )

# sns.move_legend(ax, "upper left", bbox_to_anchor=(1, 1),)

fig_03.map_dataframe(annotate)

st.pyplot(fig_03, use_container_width=True,)

with st.sidebar:

st.header("About")

st.write("This webapp was developed by [murphyqm](https://github.com/murphyqm) as part of the course materials for the",

"[*SWD7: Software development in Python*](https://arc.leeds.ac.uk/training/courses/swd7/) course run by the [Research Computing Team](https://arc.leeds.ac.uk/about/team/) at the University of Leeds.")

st.write("Find out more about [Research Computing](https://arc.leeds.ac.uk/) at Leeds.")

st.write("You can also get in contact with me directly by leaving a message [here](https://murphyqm.github.io/murphyqm/).")

st.write(r"$\textsf{\scriptsize Authored by Dr Maeve Murphy Quinlan, University of Leeds Research Computing Team © Copyright 2024}$")

st.write("[Research Computing Team](https://arc.leeds.ac.uk/about/team/) | [Research Computing Website](https://arc.leeds.ac.uk/)")